Political cartoons have been a staple of American journalism — and indeed democracy — since the country’s founding. Benjamin Franklin’s 1754 “Join or Die” woodcut depicting a snake spliced into eight segments representing the American colonies is widely considered an early masterpiece of the genre. But with the downsizing of traditional print media in recent years — thanks to the rise of social media and other online platforms — cartoonists have had to find new channels for their art form. Felipe Galindo has spent nearly half a century reflecting the world around him through his art. A native of Cuernavaca, Mexico, Galindo moved to New York 40 years ago hoping to break into the profession. Since then, his work has appeared in numerous publications, including The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and many others. For Galindo, the power of political cartoons lies in their ability to help viewers “find the unexpected in the everyday.” He spoke with EMS about his work and its role in today’s political climate.

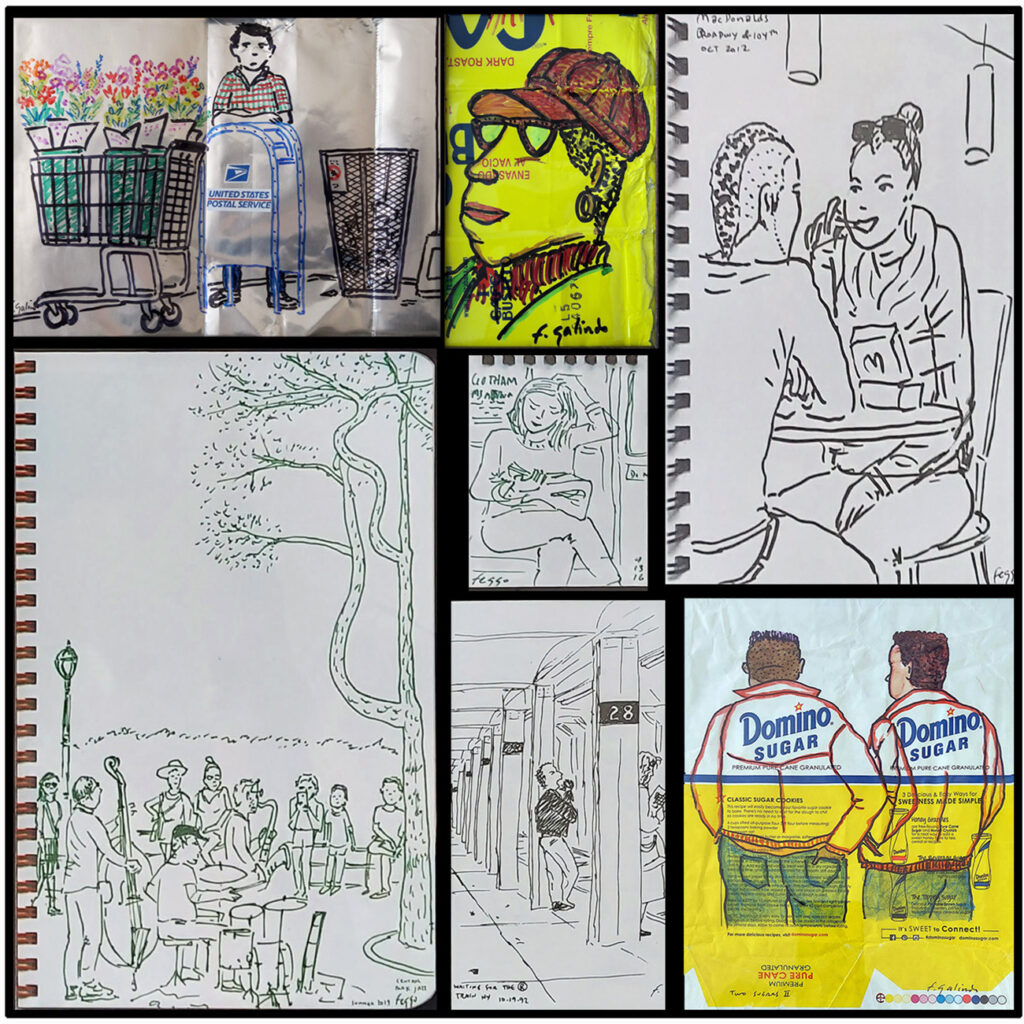

You’re hosting an exhibit of sketches you’ve created during your four decades living in New York. What’s the central idea behind the event?

I’ve been developing works related to my sketches called Use Reuse, where I incorporate my sketches with disposable materials. I’m increasingly concerned about the environment and the garbage we create, so in these works I try to take a creative approach to highlighting all these materials that we throw away. But I also wanted to show where all my ideas came from. I’ve been sketching for more than 40 years. I use these sketches like a camera to take down quick ideas when an image strikes me. It’s a sort of a visual diary.

What strikes you when you look back at some of your older sketches?

I notice how the city has changed. When I moved to New York the city was in really bad shape. I was coming from Mexico City, so arriving in New York was like walking onto a movie set. But New York is safer and more welcoming now than it used to be, and the people are friendlier. New York used to be more hostile.

What is the landscape like now for political cartoonists. Is the medium struggling?

The profession has changed… it used to be more specialized. There were cartoonists who did just humor. There were editorial illustrators, syndicated cartoonists who used to appear in many papers. There is still variety in the profession, but political cartoonists have suffered because of the shrinking of the media. I recall the 2008 financial crisis. I lost 75% of my clients. It was brutal, but I’ve since found new outlets. And there are always new generations who try to give voice to what is happening. It has to do with passion. If you want to do it, you do it and you will find an outlet.

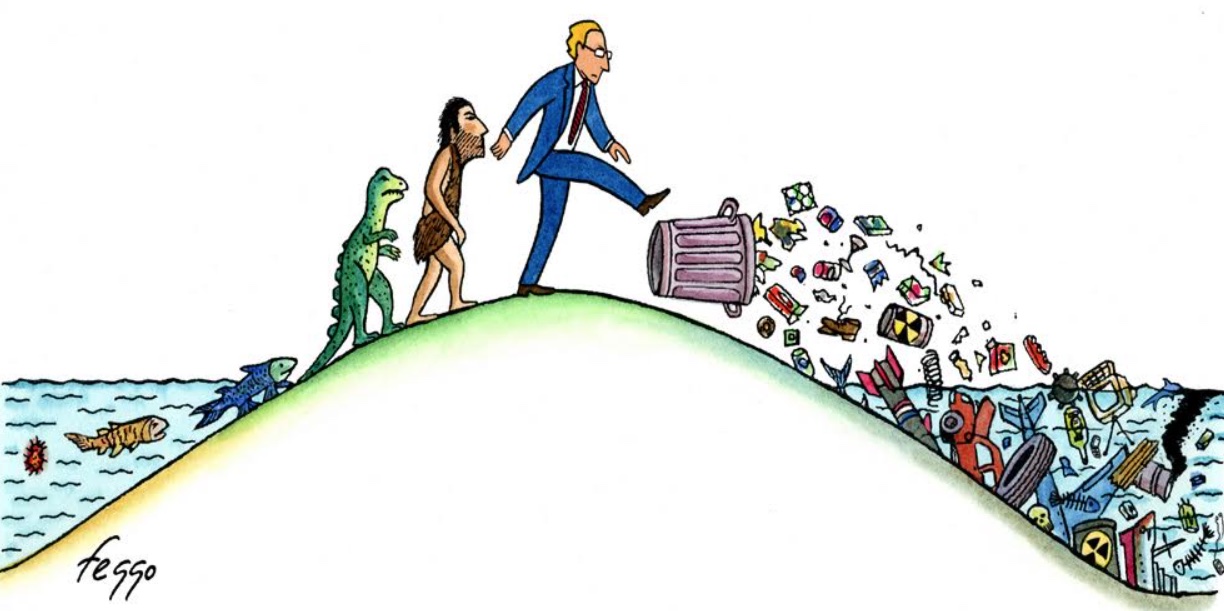

What are some of the major themes that you tackle in your illustrations?

I do images about social justice, about discrimination, about the environment. These are important to me. During the Trump years I did a lot critiquing his policies. And I have to confess, after Trump left office, I felt burned out. Then Covid came and I struggled to find images. It was a moment of reckoning for me. But thanks to a group I became part of, where we do what we call Cartoon-a-thons (sort of like hackathons where cartoonists compete to come up with new ideas) and where a lot of the focus is on these issues, the ideas began to churn again. It got me out of my writer’s block.

You mention discrimination. Have you encountered this in your professional life?

When I came to New York there were a lot of people in the profession wondering, Why is this Mexican coming here trying to break into the American market. It was still the Cold War and so there were many illustrators from Eastern Europe. Seeing a Mexican trying to do that… well, I answered with my work. Your work will open the doors for you and get the respect you want. I remember going to the New York Times with my portfolio. The security guards at the door told me the messenger entrance was around the corner. And I responded that I’m an artist. Just two years ago I was teaching at a university and again, security would ask for my ID before letting me on campus. So there is this systemic racism. But I’ve also encountered people who are supportive and accepting. It goes both ways.

How do you find humor in the subjects you cover?

Through humor you can see the world in a different way. And there is a broad range of humor — from satirical to ironic to supportive — in our field. In my case, I’ve always liked surrealism, which allows you to find the unexpected in the everyday. So, I wouldn’t say its humor so much as reflection.

Political cartoons can often transcend language and even cultural barriers. Can they transcend the political divides we see now in this country?

Cartoons started in the late 18th century as a critical voice against kings, against religious leaders. It was always a critical voice. But the murder of the French cartoonists (working for the French satirical Magazine Charlie Hebdo in 2015) was something of a watershed. They were really pushing the boundaries of freedom of expression… and instead of a dialogue, extremist groups resorted to arms. That really permeated into our profession… should we have limits, should we self-censor. And I would say, we have to be more aware of what we are doing, who we are criticizing. I think we have to be very respectful of what we are saying, especially when it comes to oppressed groups and minorities, especially in these divided times.

What advice do you have for young, aspiring cartoonists?

Your passion is going to guide you. But you have to have a thick skin. Take rejection as a creative challenge to come up with a response through your work. When I taught cartooning, some of my students wanted to do political cartoons and I would tell them to start sending samples or to approach local papers, even in their own neighborhood. Talk to them, even if it means working for free at the beginning because that way you build a portfolio. And it helps you develop your voice. Knocking on doors will eventually open doors. And practice, practice, practice.

An exhibit of Felipe Galindo’s work, “Sketching New York (and the World) 1982-2022″ will be on display in New York at The Interchurch Center, Treasure Room Gallery, 61 Claremont Avenue (@120th Street) Train #1 to 116th St. Details below:

OPENING RECEPTION: THURSDAY SEPTEMBER 22, 6-8PM.

EXHIBITION ON VIEW: September 22-October 28.

Free and open to the public, everyone is welcome.

GALLERY HOURS: Mon-Fri 10am-5pm