In the North Carolina city, Hispanics are attending public hearings to speak out about why they want electoral maps to be redrawn. Meeting informally around a kitchen table, they told Spanish language media reporters what they would have told the hearings if they had had the chance.

Also available in Spanish

In mid-September, more than 100 people filled an auditorium at Durham Tech Community College as part of the public hearings that the North Carolina General Assembly has been holding to discuss redistricting based on 2020 census data.

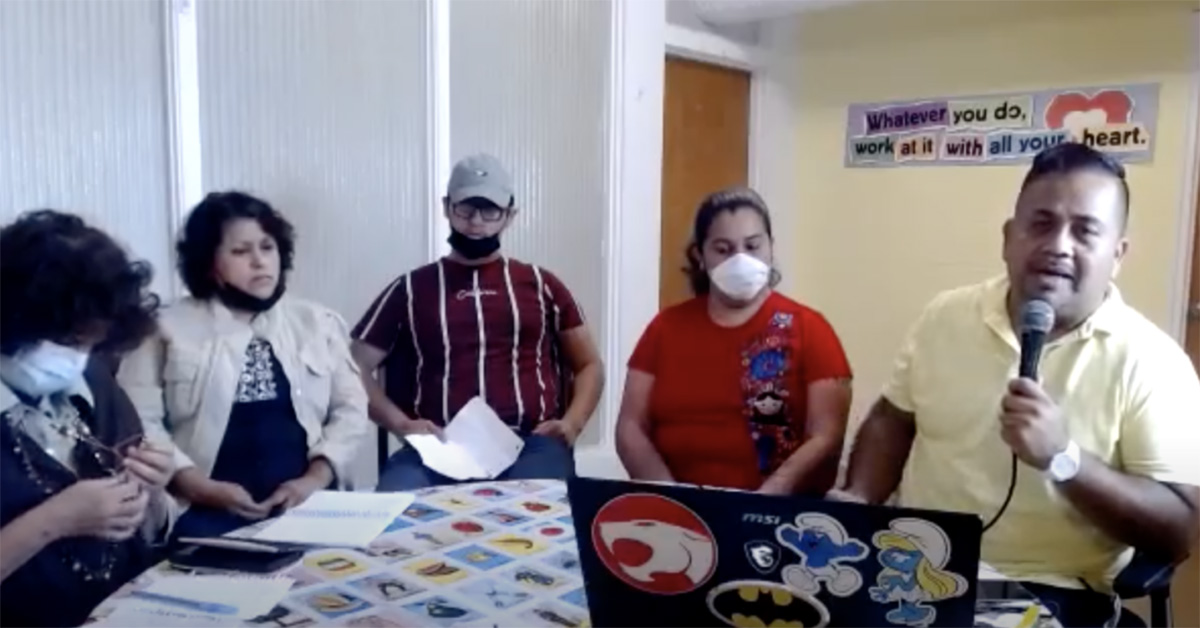

A group of Latinos led by veteran community organizer Ivan Almonte from Rapid Response, attended the event to express their views on the redesign of electoral districts that happens every 10 years.

“Many Latinos in Durham feel invisible and powerless when it comes to influencing institutions on issues that matter to families and that are for the well-being of the people,” Almonte said during an informal conversation at his home, with four Latino community activists. The event was organized by Ethnic Media Services for Spanish language media reporters.

“Unfortunately, the event was at a time when not all the working class people, the most impacted by the redistricting, could go, everything was in English and there were no interpreters … There was very little space and with almost 30 politicians there, not all community members could get in,” said Almonte, who’s been demanding more hearings take place in the neighborhoods.

Undocumented

Durham is the fourth fastest growing city in North Carolina and the Latino community increased by 40% in the last 10 years. But many of them are undocumented, are facing rising housing costs due to gentrification and remain in the shadows despite living there for more than two decades. Across the state only seven counties do not cooperate with immigration authorities, keeping many Latinos afraid of interacting in public spaces.

“They (undocumented) don’t want to drive long distances to go to hearings because if the police stop them, they can go to jail and end up being deported,” Almonte explained. “But it is important to participate because what happens in the next 10 years can have a negative or a positive impact on everyone’s lives. Durham is our home.”

Education

For Patricia Obregon, mother of four and community organizer involved with public schools, one of the main investments the state should make in the next decade is education.

“The schools have no resources, there are too many students per class, there is a lack of after-school programs, and there are no interpreters and not enough teachers for children with disabilities,” Obregon said. “Before the pandemic the superintendent of public schools had meetings with us, but he always told us that there was no budget for everything that is needed.”

Although there is a Latino representative on the school board, Alexandra Valladares, activists believe that more voices are needed to highlight the mental health needs many families have had during the pandemic: neither telemedicine nor virtual education have been accessible to Latinos given the gap in technology access for low-income communities.

Angel, 18, the son of a community organizer, represents young people in these spaces. He said his generation should be prioritized in school budgets. “Could you teach us in schools about ethnic studies? We are the people who are going to change the future,” he said.

Mental Health and Domestic Violence

Casilda Jaimes has worked with women victims of domestic violence and said that there are no programs that allow them to heal after these episodes, and the few that do exist are not offered in Spanish.

“A counseling program for Hispanics that offers a mental health service in Spanish is so important and it is a topic that is never discussed and for which we have no access,” said Jaimes, for whom attending therapy with an interpreter is “impossible.”

Housing

Laura Naine has worked 20 years with the community doing research interviews and visiting neighborhoods where low-income minorities live. Housing tops the list of her concerns. She has encountered unsanitary homes, poorly lit and unpaved streets, and public spaces without any maintenance. Durham City Hall promised an app for residents of these neighborhoods to voice their complaints, but it never worked.

“Public officials should do more due diligence and have more inspectors to supervise these houses,” Naine said. “There is no maintenance and people pay rents of $500 and up … That it is discriminatory because if someone from another community needs a service, they immediately solve it.”

The pandemic has also impacted Hispanic families who, despite the rent moratoriums, were forced to leave their homes due to job loss and moving to neighborhoods with high crime rates. Without documentation, many of these families do not have access to public or affordable housing programs.

Discrimination

“The political climate is very ugly in some counties,” Almonte said. “Burlington is the most racist county in the entire state, and Durham is the most progressive and liberal, but we are only 30 minutes apart and there is a history of arrests and raids there… our allies have always been the communities of color that defend immigrants.”

The organizers mentioned how this hostile environment of discrimination worsened when Donald Trump was elected. “People unloaded and opened their racism wallet,” Jaimes said. “They felt allowed to say, ‘we are white’, ‘we are supreme’ with words and hurtful looks, a lot of negativity.”

Despite the barriers, the community is “waking up” and “feeling empowered”, which makes politicians afraid of what they can achieve. “They are afraid that we realize how capable we are of making changes; they want to leave us behind and make sure that no one sees us,” Obregon said.

“But that encourages us to raise our voices even more,” added Angel.

Almonte closed the meeting inviting the community to “not be afraid to talk to your neighbors”, and to help create neighborhood committees “to educate everyone on how to navigate the system because it is important to be united, not to be fearful. What we do, comes from our hearts because we are impacted by these problems and we need to fight for fair redistricting,” he concluded.