A new study of racial representation in U.S. school books by The Education Trust holds that numbers alone don’t cut it: To change unequal representation for people of color is to change not only how many are portrayed, but also how they’re portrayed.

It’s a uniquely qualitative approach. Racial diversity in books may and should increase over time, but if characters of color are represented simplistically, stereotypically, or negatively, these books disservice U.S. grade students, over half of which are now non-white.

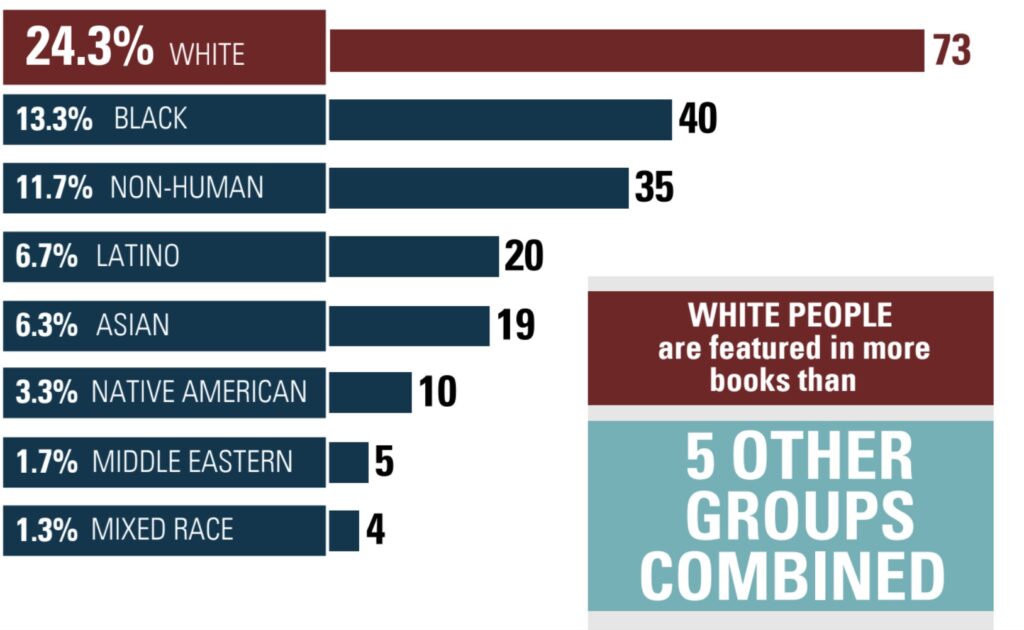

Representation gaps

The study, published on Thursday, September 14 and written by Drs. Tanji Reed Marshall and William Rodick, reports numbers to support this disservice: Among 300 U.S. grade school books — randomly chosen, evenly across grade levels, from publishers commonly used in English language arts curricula like Scholastic and Penguin Random House — nearly half of the people of color are portrayed negatively.

This portrayal takes many forms: Individually, people of color are often portrayed as “one-dimensional” or without agency, per the study; groups or cultures of color are often portrayed with associated stereotypes or as lesser than others; and historical or social topics are “almost always sanitized, told through a singular perspective.”

“There has always been representation in curricula — and that representation is predominantly white,” said Dr. Marshall. Those wanting to fill representation gaps, “must also push for including books with characters of color who are fully realized and positively represented.”

This imbalance extends to the creators of the books themselves: 232 of the 300 books had at least one white author or illustrator (77.3%), 6.8 times more than the next-highest category: Black creators, who were involved with 34 books (11.3%).

Determining complex representation

The study divides the criteria it uses to determine complex, partial, or limited representation between three categories: historically marginalized individuals, groups or cultures, and historical or social topics.

On the level of individuals, questions are suggested of their multidimensionality, agency, and (positive or negative) influence; those of groups or cultures include stereotypes, positive assets, and value in relation to other groups; those of historical and social topics include sanitization or oversimplification, inclusion of historically marginalized perspectives, and relation of the topic to students’ experiences.

280 of the 300 books had central characters, essential to the story or information. Of these, 124 had people of color (44%). Only 53% of these people were portrayed with complexity, however, while another 44% had limited representation.

Dr. Rodick said “At first, we were pleasantly surprised that half of the characters of color were represented with complexity. And then we were surprised that we were surprised, because that’’s such a low bar. We want far more than just half. We were also surprised at how rare overlaps of identity were, including varying family structures, genders, disabilities, relationships with the carceral system — those stories were still very much hidden on the page.”

118 of the books had groups of color (39%), with less than a third of these (31%) doing so with complexity “by avoiding stereotypes, immersing people in culture, and portraying groups of color positively and as equally valuable to other groups,” per the study. Over half did not (54%).

On the sociohistorical front, 137 books involved historical or social topics (46%), and few did so with complexity (16%) “by avoiding sanitization, including a marginalized perspective, and connecting the topic to student realities.” The vast majority did not (80%).

“Like the rise in bans of books which may expose students to diverse representation, imbalances in this representation is not new,” Rodick said.

PEN America reports 1,477 individual U.S. book bans during the first half of the 2022-2023 school year — 28% more than the prior six months. 40% of books banned from July 2021 to June 2022 had protagonists or prominent secondary characters of color; 21% had titles indicating race issues.

Examples of such banned books include “I Am Rosa Parks,” “I Am Martin Luther King, Jr.,” “The Bluest Eye” and “The Hill We Climb.”

Although greater representation is an uphill battle on the legislative front, some states like Illinois — which, in June 2023, became the first to pass a ban on book bans — and California, which passed a similar bill in September — are making historic progress.

“As we work toward more freedom in this nationwide,” said Rodick, “We’ll be using our report as a basis to work closely with publishers, teachers and curriculum advocates to make guides for reviewing what kids are reading, understanding the limits of how people, groups, and topics are portrayed in these books, and deciding how to present these books for the fullest understanding of what’s being portrayed.”

Balancing limited representation

“An increase of Black characters in children’s books is great,” said Rodick, “but we want to push beyond the count — not just whether they’re portrayed, but how often they’re portrayed in negative ways.”

“We don’t want anyone to remove or censor any books on the basis of their representation, or deem them bad or good; many which are limited are of indispensable value,” he continued. “We want to recognize the value of these limited books by adding more perspectives to them, to engage students with them more deeply. If a book presents a topic in a very problematic way, it’s not about whether the reader should approach it, but how they can approach it best.”

One of the books examined, for instance, is the autobiography “Ruby Bridges Goes to School.” In it, Bridges frames racial segregation as a personal issue, whereby certain white people think they should not befriend Black people.

Per the study, a more complex view of an adjacent topic is presented in the picture book “Nasreen’s Secret School,” set in Taliban-ruled Afghanistan. In the story, the eponymous girl’s parents disappear and the regime forbids her to attend school and leave the house without a male chaperone or burqa. In defiance, Nasreen’s grandmother enrolls her in a secret school, where the girl takes solace in an outlawed world of art and literature at the encouragement of her teacher.

That Ruby Bridges’ personal perspective conveys a more limited representation of educational segregation than Nasreen’s does not mean that it isn’t an invaluable way to learn about it, Rodick emphasized. It does mean, however, that readers would learn more about it if the book were taught with others which present segregation in its social, economic, or legal dimensions, beyond this personal limitation.

In short, representation doesn’t stop at a mirror.

“We engage students not only when they can see themselves come to life on the page, but when they can see others come to life on the page, when they can step into others’ worlds through their experiences,” said Rodick. “A whole understanding of the people who have these experiences, however, you can’t get that through a single story — by anyone.”