SAN FRANCISCO — Eighteen months ago, Margeret Wilson walked out of jail. A mother of five and legally blind, she faced the unimaginable challenge of rebuilding her life and that of her family post-incarceration.

Recently expanded Medi-Cal services mean women like Wilson can now access a wider range of support as they work to regain their footing.

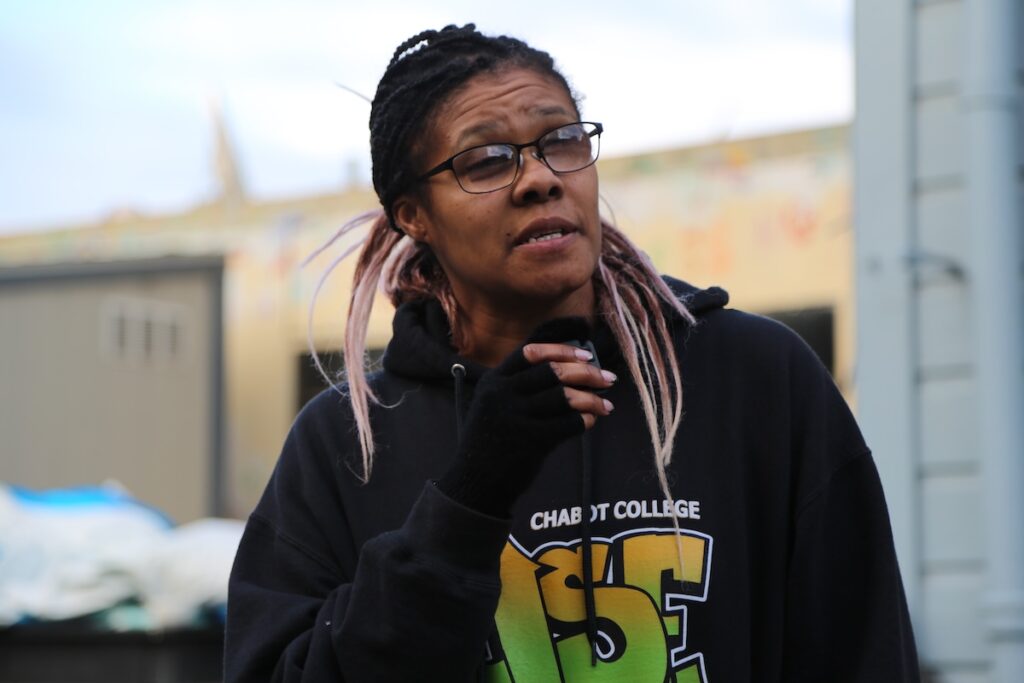

“In 2021 I was arrested,” says Wilson. “After I got out on bail, I came into this program,” she continues, referring to Cameo House, a residential program for reentry women and their children located in a non-descript apartment building in San Francisco’s Mission District.

“This place shows that not every person who is incarcerated is just a piece of paper or just someone who has no worth,” she adds.

Currently enrolled at Chabot Community College in Oakland, Wilson is now working toward her bachelor’s degree in sociology. She’s also employed as a transitional housing ambassador with the non-profit Five Keys, which operates shelters and homeless navigation centers in San Francisco and Alameda counties.

Wilson, who has resided at Cameo House with her youngest son since her release, joined a gathering here Wednesday of representatives from community-based organizations, ethnic media journalists, as well as other formerly incarcerated women who shared their personal stories of trauma and pain but also of hope and healing.

The event, organized by Ethnic Media Services in partnership with the Department of Healthcare Services, highlighted the range of newly available health services under Medi-Cal for reentry women, children and families.

Nearly one million women in the United States are currently under the criminal justice system, around 10% of them behind bars with the rest either on parole or probation. A majority are women of color.

In California, there are some 3,900 women currently serving time, according to the latest figures. It is less clear how many women are currently out on probation or parole. Statewide, some 458,000 individuals are either behind bars or otherwise under the criminal legal system.

Health data on women caught in the justice system paint an alarming picture: a majority have at least one child and are survivors of childhood abuse or trauma themselves. Many also face the ongoing threat of domestic partner violence. Women in jail also report higher rates of mental health and substance use disorder than their male counterparts.

“I am working on my recovery,” says Shannen Curlin, a single mom and current resident at Cameo House. “I am a couple of weeks shy of two years. I’m just trying to get my priorities in order, go to school, get my record lifted and just trying to straighten up and fly right.”

Curlin lives with her 10-year-old son.

“They took me in and allowed my son to come here with me. They supported me with graduating high school and starting college. They helped me clear my DUI and my record. They pressed me to make sure I go to my groups and that I am participating in my mental health and in my recovery.”

Starting in 2023, California became the first state in the nation to offer federally subsidized healthcare services to incarcerated youth and adults up to 90 days prior to their release. The Justice-Involved Initiative, aimed at easing the reentry process, is part of a broader expansion in Medi-Cal services built on a “vision of healthcare that is not stuck in hospitals but goes to the communities to close the gap,” says EMS Director Sandy Close. “Especially for people who have never had access to healthcare.”

For the women at Wednesday’s event, housing was the number one issue, one not typically linked to public health. And yet Medi-Cal enrollees can now receive housing navigation services covered as a benefit under the program.

“My doctor referred me to a case manager,” explains Wilson. “And they help with housing. So, I met the gentleman… and he let me know that my Medi-Cal was inactive, and that I had to get this taken care of because it’s what pays for all the services.”

Wilson shared that she’s since continued to meet with her case manager as she prepares to transition out of Cameo House.

Tina Curiel runs communications for the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice, which operates Cameo House. “It is one of San Francisco’s only alternative sentencing housing programs that women and children can live in and for that long. It is unique in that way.”

Residents –around 15 women and their children currently – can remain for up to 18 months.

“To hear statistics of women and children, there’s like a few thousand per each bed available in San Francisco,” notes Curiel. “So, it’s ridiculously underfunded, these types of programs.”

Other speakers included Janelle Buccat, program manager with the Occupational Therapy Training Program in San Francisco, and Michelle Alvarez, program director with Instituto Familiar de la Raza.

Alvarez described how her organization uses Medi-Cal dollars to fund “wellness activities” for low-income families, including kayaking trips on the San Francisco Bay and visits to nearby Muir Woods. For families and kids “struggling with anxiety, depression, or worrying about how to pay rent,” she adds, such activities are a balm for their mental well-being.

Charity Harris is program director with Cameo House. “This is a second family for me,” she told the gathering. “This work gave me purpose at a time in my life when I lost purpose.”

She continued, “Seeing the impact of the criminal justice system on these families inspired me to come forward.”