Above: Leonila Alvarado has worked the fields in Fresno for more than two decades and says it is critical that work stop when temperatures get too high. “The heat can kill,” she says. (Credit author)

“The weather has changed dramatically here. The heat is more intense, and this puts us at greater risk,” says Martín Melchor, a farmworker who has worked the same fields cultivating grapes, almonds and peaches in Fresno, California for the past 34 years. “We have to take rigorous precautions in order to protect ourselves.”

Originally from the state of Jalisco, Mexico, Melchor is the “mayordomo” – manager – of a team of farmworkers here.” Part of my job,” he says, “is to monitor the temperatures regularly. When we know it’s going to get hot, we try to start work earlier.”

And hot it has been. Fresno isn’t known for its mild climate, with temperatures – especially in the summer months – often nearing or surpassing triple digits. But with the impacts of climate change the heat is growing more intense, with the past 10 years being the hottest on record, according to the National Weather Service.

Risks of extreme heat

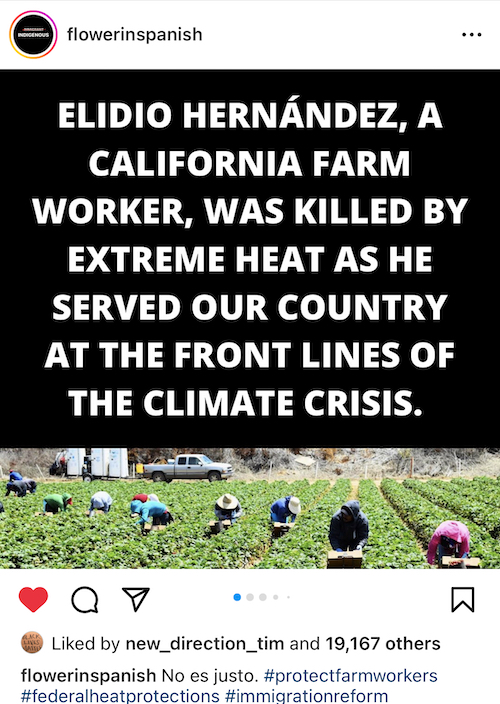

The risks of extreme heat for farmworkers in Fresno – located in California’s Central Valley, where much of the nation’s fruits and vegetables are grown – were laid bare earlier this month after the death of Elidio Hernández, who died working in temperatures that exceeded 100F.

Shortly after his death was announced, an Instagram account popular for defending the rights of farmworkers in the state posted a statement declaring Hernández died as a result of the “extreme heat while serving this country on the front lines of the climate crisis.”

A forensics report determined that Hernández died from cardiovascular disease, noting that there was no evidence showing extreme heat played a role in his death.

Nevertheless, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warns that exposure to extreme heat can compromise the health of individuals with cardiovascular issues. According to one report, “temperature variability (large changes in the average temperature of a given region over a particular time period) may also influence cardiovascular morbidity.”

Hernández’ death has prompted calls from the United Farmworkers Union and US Senator Alex Padilla for better protections for farmworkers as temperatures continue to climb.

Melchor says working in temperatures above 90F is “unbearable… it’s very dangerous, and here we recommend stopping work because the symptoms (of heatstroke) can come on immediately.”

Staying hydrated, staying vigilant

Leonila Alvarado has worked the fields in Fresno for more than two decades. Originally from Oaxaca, Mexico, like Melchor she manages a team of farmworkers and says it is critical that work stop when temperatures reach into the triple digits because “the heat can kill.”

At 6:15 a.m., on the side of the road in front of a ranch in Fresno, Alvarado is loading bulky drums of water onto her pickup truck. The water is for the farmworkers under her charge, she explains, noting that as manager her most important responsibility is to watch over the health of her colleagues, making sure they are informed about the risks of high heat, and that they stay hydrated and “follow all the recommendations to avoid serious problems.”

And what are those recommendations?

“Every Monday we have meetings with colleagues and usually the main topic is precautions for the heat,” says Alvarado. “We recommend that workers drink water every 15 minutes. A lot of people say they’re not thirsty, but that doesn’t matter. You have to wet your lips with one or two sips. Waiting until you are very thirsty before you drink can lead to dehydration before you even know it.”

There are workers, Alvarado says, who because of the heat drink large quantities of energy drinks or sugary beverages. “It’s important to remind workers that the healthiest option is to drink water, without sugar.”

When it comes to clothing, workers have to protect themselves from the pesticides and chemical agents prominent on many industrial farms, “but one has to wear the lightest clothing one can,” Alvarado stresses.

Alvarado’s workday typically starts around 6AM and ends around 2:30PM. She says when they know it’s going to get hot, workers try to finish the harder jobs – like shoveling – as early as possible.

One problem she encounters has to do with workers drinking alcohol over the weekend and coming to work on Monday hungover. “This is very dangerous, because they are already dehydrated. I realize it right away and tell them that it doesn’t bother me, that they should tell me the truth, and I’d rather they stay home to rest so they don’t get sick here.”

What to watch for

What are the signs that a worker might be feeling unwell?

“This happened recently with a lady who felt sick because of the heat. The symptoms are sweating, reddening of the skin, shivering in the body; they feel nauseous, sometimes there is vomiting,” Alvarado explains, sounding more like a medical expert than a farmhand.

She says vigilance and decisiveness are key when a worker shows signs of heatstroke.

“The first thing is to take off some of their clothes and then put the person in a place as cool as possible. We have a tent to protect us from the sun. But we can also take the person to an air-conditioned car. It is important to be vigilant. If the person doesn’t get better soon, you have to call 911.”

Alvarado, one of only a handful of female managers in the area, acknowledges the difficulty of the work. “We try to perform well in the work we are asked to do,” she says, “it is hard but there is no other way.”

This story was produced as part of a collaboration with the Office of Community Partnerships and Strategic Communication for their Heat Ready CA public awareness and outreach campaign. Visit Heat Ready CA to learn more.