For weeks Leah Han’s mother pressured her to put money into a new investment opportunity. Initially reluctant, Han eventually agreed on the condition that she first meet her mom’s contact to ensure things were legit.

That meeting would lead to an ongoing campaign against the man Han says was involved in an alleged multimillion-dollar cryptocurrency scam targeting Atlanta’s Korean community.

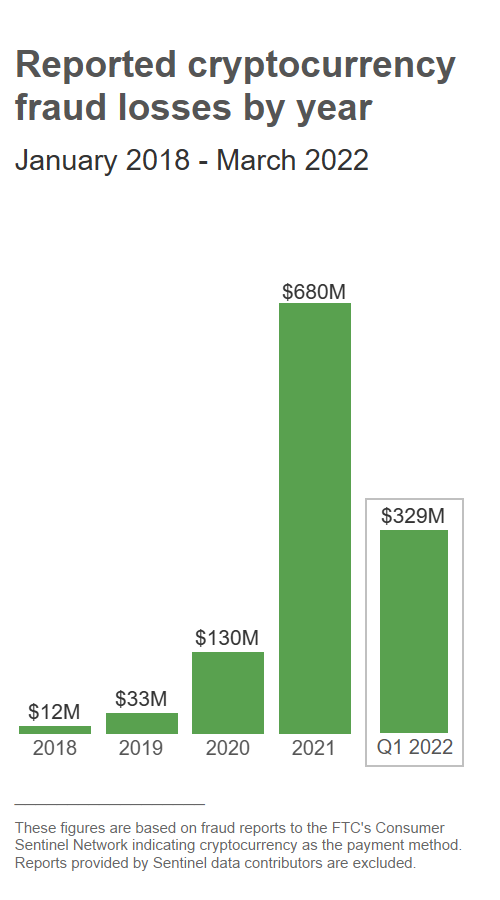

Data from the Federal Trade Commission show such scams are part of a larger national trend that last year alone cost consumers — many of them in immigrant communities — upwards of $1 billion.

“He was so flashy,” recalls Han of that first meeting. “I got to the hotel, and I saw about 60 to 70 people waiting for him in the lobby. They all had cash money. They were all Korean.”

According to Han, in 2020 her mother, Jean Choi, met with an individual who introduced himself as regional manager of a Canada-based internet investment firm called Club Mega Planet. (We are withholding the man’s name pending ongoing legal proceedings.) Han’s mother was told that to invest she had to first become a member by purchasing points from other members. Han described the point system as something akin to “chips in a casino.”

The money from these purchases would then ostensibly be invested in a cryptocurrency exchange, which Han’s mother was told promised monthly returns as high as 30%.

Interested parties were encouraged to invest in larger increments — upwards of $10,000 or higher — for better payouts, says Han, adding that to redeem the points members had to sell them, either to new investors or, as was often the case, back to the individual at the center of it all.

“He operated like a bank,” she says, “only he never paid in cash, only in cryptocurrency, and there were never any receipts.”

Reporting by the Korea Times in Atlanta shows these initial payouts encouraged buy in from larger numbers of people in the community — most of them older retirees — with word spreading primarily through church and social groups.

A promotional video posted to YouTube attempts to explain how the system works.

Han says her mother’s enthusiasm bordered on obsessive, to the point that Han’s initial skepticism began to damage their relationship. “It got weird,” she remembers. So, after her meeting at the hotel she relented, thinking to herself, “how could so many people be wrong.”

Han would invest $10,000. Her mother put in close to $30,000. Several months later, in June of 2021, the website disappeared, along with much of her and her mother’s investments.

According to the Korea Times the number of alleged victims in the Atlanta area reaches into the hundreds, with estimated losses nearing $10 million.

The allure of crypto

For smaller investors — particularly in communities of color — cryptocurrency is seen as a more accessible investment option compared to traditional financial markets that are more complex and often have higher barriers to entry.

Investors poured some $30 billion into cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum in 2021.

That wild eyed enthusiasm — fueled in part by a fear of missing out on a potentially lucrative payout — has helped spawn a thriving ecosystem of scammers both online and off, many of them targeting immigrant communities.

According to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), Americans lost $1.3 billion in crypto-related scams since the start of 2021. In one especially virulent scheme known as “Pig Butchering,” victims are lured in — or “fattened” in the parlance of scammers — by individuals pretending to be romantically interested who then convince their targets to invest in sham crypto investment sites.

Elizabeth Kwok is assistant director with the FTC’s Division of Litigation Technology and Analysis. She says that based on complaint data collected by her office, young people and minority consumers are among the groups most often targeted.

“These communities may be quicker to adopt new technologies and innovations in an effort to have easier, quicker financial services, but don’t fully recognize the risks associated,” explains Kwok. “These communities also tend to have less access to more traditional financial services, which makes them particularly vulnerable to new frauds.”

That was the case with Han’s mother. “My mom is a retired senior,” she says, noting that like many older Koreans her mother, 65, lives on a fixed income with little to nothing in the way of retirement security.

“A lot of older people in the community are small business owners. They work 30 to 40 years and then retire with a little in their account. No one has like a 401k. So, when someone comes up speaking about crypto investments, seniors say, ‘I don’t know what it is, but it sounds interesting.’”

No recourse for victims of crypto scams

After her experience, Han took her case to the local authorities in Gwinnett County, who she said were initially incredulous. “They don’t know scams like this exist in ethnic communities,” she said, noting that language barriers and the sense of shame that victims often feel prevent them from reporting such crimes.

Officials in Gwinnett did not respond to a request for comment. The case was eventually reported to the FBI. Han was told not to expect a speedy resolution.

Indeed, reporting shows that victims of cryptocurrency scams are often left to their own devices. Lax regulations around the crypto market and the nature of cryptocurrency itself also make it near impossible for victims to recover their losses.

“Cryptocurrency’s decentralized nature means that there is no middleman by design,” the FTC’s Kwok explained, “so there’s no ability to reverse the transaction for a defrauded consumer. Essentially, this is the same situation as if you were to have lost cash on the street.”

The FTC maintains an informational page on its website warning consumers about the prevalence of cryptocurrency scams. The page is available in both English and Spanish.

Georgia’s attorney general also recently released a Korean translation of its Consumer Protection Guide for Adults.

Jongwon Lee, an Atlanta-based attorney who worked with Han as she pursued her case, says it’s “rare for the state attorney general’s office to publish scam information for non-English speaking Asian populations.” The guide, he notes, is “evidence that the state’s top officials are starting to take the issue of scams in the Asian immigrant community more seriously.”

Seeking justice for victims

For Han, the goal now is to bring the man responsible to justice.

In March, she published an ad in local Korean media in Atlanta alerting residents to the scam’s she alleges he was behind. She has also been working to connect with other alleged victims, both in Atlanta as well as in other cities nationwide, gathering testimonials as part of a mounting pile of evidence that she has shared with law enforcement.

“I was invited to an orientation meeting to learn about Club Mega Planet,” wrote Atlanta resident Je Dong Woo, who lost $73,000. He was among those who shared their stories with Han. “At the meeting I saw several prominent people from the community, including a well-known pastor. They were talking about huge returns while spreading God’s glory. I felt I could trust it.”

For Han, these stories speak to the psychological toll such scams inflict. “They break up families and communities,” she said. “These seniors go to church; they recruit church members. And when the system collapses, they become depressed. They have to leave their church.”

In an interview with the Korea Times, the individual denies any wrongdoing, claiming the accusations against him are “nonsensical” and that anyone with a complaint should seek redress with local law enforcement.

Attempts to reach the individual for comment through publicly available phone numbers were unsuccessful.

Han says soon after publishing the ad the alleged perpetrator fled to California, where he later declared bankruptcy, listing several alleged victims as creditors. An August ruling from the US Bankruptcy Court Central District of California shows his case was denied.

Han, who shared testimonials with the bankruptcy court in California, is convinced that he continues to hold substantial wealth, including several properties and cryptocurrency valued in the millions. She also alleges that he is continuing to run scams using bogus websites developed by a larger network.

But she says that after months of sleepless nights, her mother has given up on trying to recoup her lost investments. “Now she just wants to lock this f****er up.”