Editor’s Note: War, famine, and climate change are once again driving a surge in migrants seeking entry into the European Union, which legally is required to assess asylum cases before removal. Yet in EU member nation Croatia, an ongoing policy of illegal and at times violent pushbacks has human rights groups sounding the alarm.

ZAGREB, Croatia – One of the European Union’s longest borders runs along hundreds of miles of deep forest separating EU member nation Croatia on one side, and Bosnia and Herzegovina on the other. For anyone with EU citizenship, the scenery is stunning.

But for migrants and refugees trying to enter the EU, “the jungle” – as many call it – can be both a blessing and a curse.

“We hide in the woods on our way to the border, but there are many difficulties along the way, such as snakes and the danger of getting lost in the darkness at night,” says Amar (not his real name), who is originally from India. Unexploded ordinances and landmines, remnants from the 1992-95 Bosnian War, add to the risks that migrants face.

According to the EU border agency Frontex, irregular migration into the EU – refugees and migrants entering the bloc without documentation – is rising sharply, nearing numbers not seen since 2016, when estimates reached as high as 1.6 million. War, famine, and climate change are among the drivers behind this latest surge.

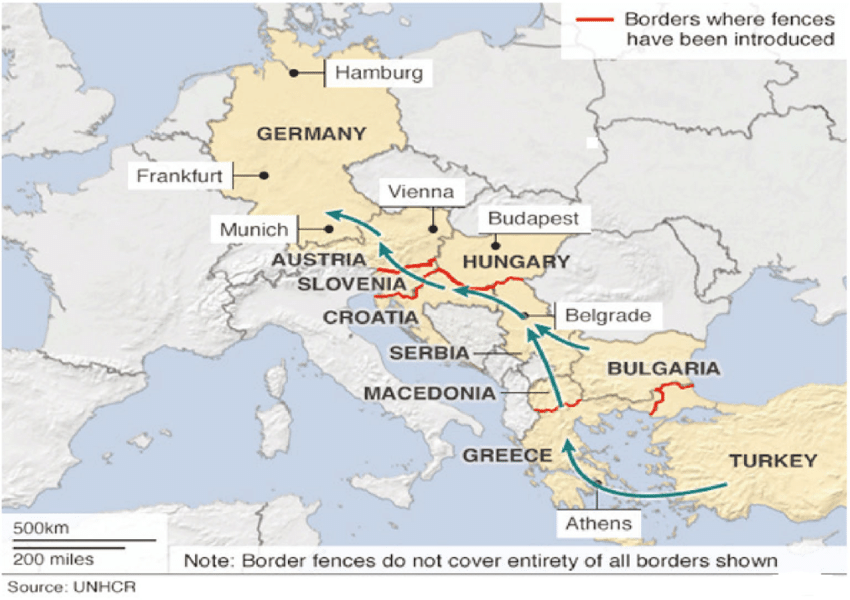

A majority arrive along the so-called “Balkan route,” which runs northwest from Turkey, through Greece and into the Balkan nations that form the southern border of the 27-member EU. In 2015, the route became a key artery for migrants from the Middle East and Africa. But after Croatia, Slovenia, and Serbia closed their borders, Bosnia and Herzegovina emerged as the region’s most important transit country.

Since 2018, some 87,000 migrants have arrived in the country. The surge comes as renewed tensions stemming from the 1992 Bosnian War are beginning to reemerge.

“Ten times in a row.” That’s how many times Amar has tried to make the crossing, and each time, “the police would catch me,” he says. Another migrant, from Iran, says he has made more than 200 attempts.

Amar lives in Camp Lipa, a Temporary Reception Center (TRC) – or migrant camp – in the northwest corner of Bosnia and Herzegovina that was opened last year after the country came under fire for its treatment of migrants. The camp sits a few days hike from the border with Croatia, along rugged terrain that while heavily monitored also allows opportunities for migrants to slip through undetected.

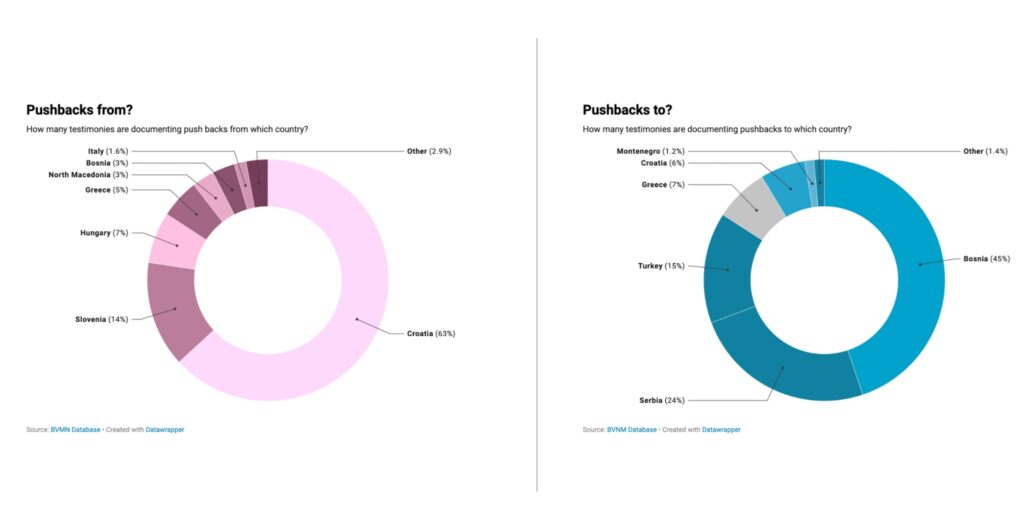

Still, reporting shows that Croatia – along with neighboring Greece and Romania – has carried out hundreds of illegal pushback operations, forcibly returning migrants like Amar back across the border. In one documented case from 2020, Croatian authorities forcefully removed more than 2,000 migrants in the span of 19 days.

The operations have raised alarm bells among human rights groups who say the EU is complicit. EU and international law require member nations to first assess an asylum seeker’s case – including irregular border crossings – prior to their removal, a principle known as non-refoulement.

Croatian journalist Yasmin Klarić has covered the pushback operations and says they are part of Croatia’s efforts to become part of the Schengen Area, made up of 26 EU countries that have abolished virtually all border controls. Croatia’s entrance into the zone would allow its citizens to travel freely across EU member countries.

Klarić believes the pushback operations are becoming increasingly normalized, and that the EU has no interest in ending them. To the contrary. “If the EU incorporates Croatia into Schengen, they will not do so despite the fact that the country is beating migrants and refugees but because it is,” says Klarić, noting a general shift in EU policy toward deterrence along its borders.

That shift can be seen in the support given by the European Commission – the EU’s executive arm – for Croatian border police, as well as in statements from leaders, including Ognian Zlatev, who represents the European Commission in Croatia. “If people try to cross the border irregularly,” he says flatly, “this is a crime.”

Meanwhile, with a global food crisis exacerbated by the war in Ukraine and simmering conflicts in Africa and the Middle East, the stream of migrants continues, fueling an ongoing humanitarian crisis along the EU’s southern border.

“Border police did that,” says one resident of Camp Lipa, pointing to an injured arm. “You journalists come and report on us all the time, but nothing changes,” complains another.

Arnela Čauŝević works at a TRC in the village of Uŝivak near the Bosnian capital Sarajevo. She says despite the obstacles to entry into the EU, few migrants opt for asylum in her country. “I only know of two or three who tried to apply for asylum in Bosnia. The others go on to cross the border, even if they need 100 times to succeed.”

The camp in Uŝivak hosts mostly families, housed in containers built on soil parched by the summer heat. One family from Pakistan is already preparing for a border crossing just days after their arrival following a 15-day walk from Serbia with little food or water and a sick daughter in tow. Their goal is to reach Germany.

Another family that fled Afghanistan following the Taliban’s return to power there is also getting ready to try their luck at the border. “If we don’t manage to cross,” says the father, “we will try again.”

Katarina Machmer is a Munich-based journalist covering migration and politics.