This is the second in a three-part series about anti-Black bullying in Santa Barbara schools. Read Pt. 1 here. Click here to read Pt. 3.

SANTA BARBARA, Calif. – In Santa Barbara, a coastal city of about 89,000 residents, the Black population has dwindled from a peak of 3.27% in 1970 to about 1.37% in 2024.

In 2022, Healing Justice Santa Barbara, a nonprofit, and Page & Turnbull, an architecture firm, produced “Santa Barbara African American and Black Historic Context Statement,” a survey of how and where Black people have lived in Santa Barbara from the Spanish colonies to recent times. The report, commissioned by the city, is meant to aid in preserving Santa Barbara’s Black history.

According to the report, “… the slow progress toward greater racial equality and continuing lack of job and housing opportunities, led many young Black people to leave Santa Barbara in the late 1960s and 1970s…. While Santa Barbara’s overall population increased in the 1970s, the city’s African American and Black population decreased by 20% from 2,294 in 1970 to 1,833 in 1980, the first time the community’s numbers had dropped since the 1890s.”

In several interviews, longtime Santa Barbarans bemoaned the impacts of gentrification and the gradual “erasure” of Black presence in the city.

Wendy Sims-Moten’s father-in-law was born in Santa Barbara in 1914 and once owned a refuse business. “But time and money and bigger resources pushed them to the side,” she said. “A lot of things that were here, small businesses that were owned by African Americans, even Latinos, it’s gone…but without any regard to the historical cultures and communities that made Santa Barbara as to what it was.”

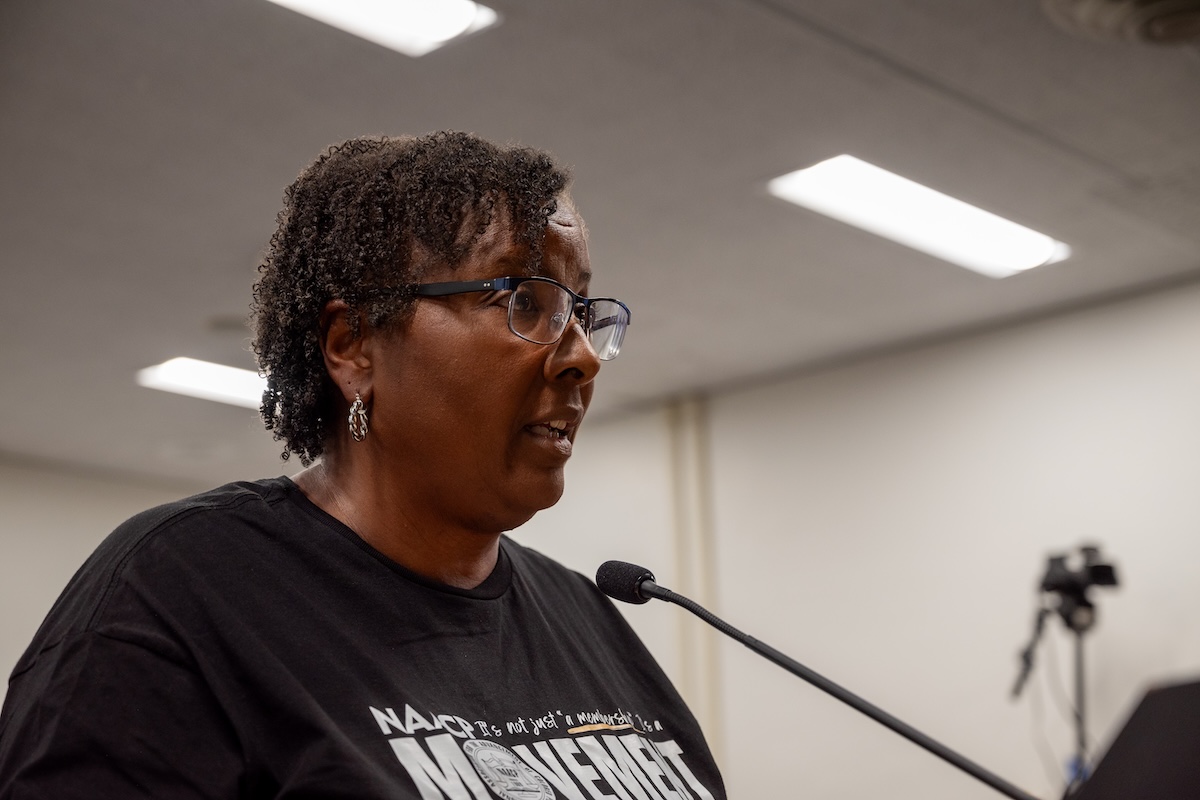

Sims-Moten, the president of the Santa Barbara Unified School District, is only the second Black person elected to that board in 53 years. Black children make up just .07% of SBUSD students.

While parents upset by anti-Black racism in the school district say that some white kids subject their kids to racist bullying, more of the incidents seem to be about racism coming from Latino kids. An ugly irony is that many of these “Black” kids being bullied are themselves mixed race Black and Mexican.

Bianca Duran’s two oldest children, a son, 14, and daughter, 13, look like their Black father. “Kids just coming out and saying the N-word and calling my daughter a monkey and saying you look like an ape,” said Duran. “Why is your hair like that and why are you dark?”

Duran, who is Mexican American, tells her children they are beautiful and to not engage with the cruelty, but it’s hard.

Leeandra Shalhoob and Shevon Hoover are among other SBUSD parents of mixed Black and Mexican American children. Whether the SBUSD counts these students as mixed race (2.5% of school population) or Black/African American (0.7%), they are micro minorities in a “majority minority” (61% Hispanic/Latino), school district. About 31% of district students are white.

These parents, as well as Latino and Black community leaders, acknowledged anti-Black racism in Latino culture.

“I won’t speak for everyone’s family or upbringing, but I know that where I grew up, there was a lot of anti-Blackness in the Latino community,” said Gabe Escobedo, vice president of the SBUSD School Board.

Connie Alexander works with schoolchildren of all races at Gateway Educational Services, the academic support nonprofit she and Audrey Gamble co-founded 15 years ago. “Unfortunately, the majority of what’s happening among negative incidents are Latino youth saying it to Black kids. Way too much of the N-word being used by Latino youth,” said Alexander, who is also president of the Santa Barbara NAACP. “Why are they using the N-word?… I really don’t know. And why it’s so painful: their perception is that the Black children are on the bottom.”

Eder Goana-Macedo, executive director of the Santa Barbara Fund, immigrated to Santa Barbara with his mother and brother from Mexico when he was four. Now 35, he came up in the public schools and knows the Santa Barbara Mexican and Mexican American communities from many perspectives.

“If you look at graduation rates, if you look at college attainment, if you take it a step further and look at who’s going where, Latinos are still at the bottom,” said Gaona-Macedo.

According to SBUSD’s 2023 “Student Outcomes Report,” high school graduation rates for Black students were 81.8% in 2020-2021 and 100% in 2021-2022, with 75% meeting requirements for UC and CSU in 2021-2022. Latino high school graduation rates rose from 88% in 2020-2021 to 93.8% in 2021-2022 with 47.5% meeting UC and CSU requirements in 2021-2022.

“There has been a lot of issues around racism in the schools. It’s not new,” Gaona-Macedo said. “You know, I went to the school where the white kids would pick on the Latino kids.”

Gaona-Macedo was offering context, not excuses, for the tensions between Latino and Black students. “So, there’s a lot of hate, and it stems from a long history in Santa Barbara between the haves and the have -nots,” he said.

The Santa Barbara Latino population, which has always been many times larger than the Black cohort, is also shrinking due to skyrocketing housing costs. Both groups are struggling to hang on in the city.

“There’s countless families in Santa Barbara where they share a household between multiple families just to make ends meet,” Gaona-Macedo said, adding, “And then you also have the undocumented factor.”

Escobedo concurred. “In the last 10 years, we’ve lost a great deal of our Latino population because of the cost of living,” he said. “Even if they work in Santa Barbara, they’re moving further and further away, sometimes out of the county…. Looking at demographic data, it’s I think about 20% of those communities have been pushed out.”

Hoover, Shalhoob and Duran blame the demographic changes wrought by gentrification for eroding cross-cultural camaraderie. In their 30’s and 40’s now, they recalled when Blacks and Mexican Americans used to hang out together, often around Black family homes on the east side of the city. But as residents have sold their houses or been priced out of rentals, those days are long gone.

“They find ways to kick out these old families. And, you know, you can’t have those backyard barbecues like you used to,” said Duran. Her children are amazed when she tells them about how Blacks and Mexicans used to hang out.

“I was like, yeah, that’s how it was. That is why there is so many mixed, you know, kids now, because that’s how it happened…. everybody was together and having fun…And we don’t have that community. And it’s not even anything that’s our fault. It’s just how time changes.”

Sims-Moten noted that children today know little of the city’s history or even America’s history of anti-Black racism.

“It’s important to maintain that history of how we become because…when community spreads out or it’s disconnected, then our children that are coming up here don’t really understand and they may be called words that came back in slavery,” Sims-Moten said. “They don’t really understand it because the history of that has been erased because that’s not a comfortable conversation…. I think erasure is a huge thing here. And we have to have those hard conversations.”

Gaona-Macedo believes families have a critical role to play, too.

“I think that’s going to take building a strong allyship between both communities. And I think we’ve started – Connie’s amazing to work with. So is Audrey and the Healing Justice organization among others,” he said. “We do need to look at how racism is rooted in some of our culture…. And as a community, we need to find ways to fight that culture.”

Pilar Marrero contributed reporting to this story.

This resource is supported in whole or in part by funding provided by the State of California, administered by the California State Library in partnership with the California Department of Social Services and the California Commission on Asian and Pacific Islander American Affairs as part of the Stop the Hate program. To report a hate incident or hate crime and get support, go to CA vs Hate.