Aging in America

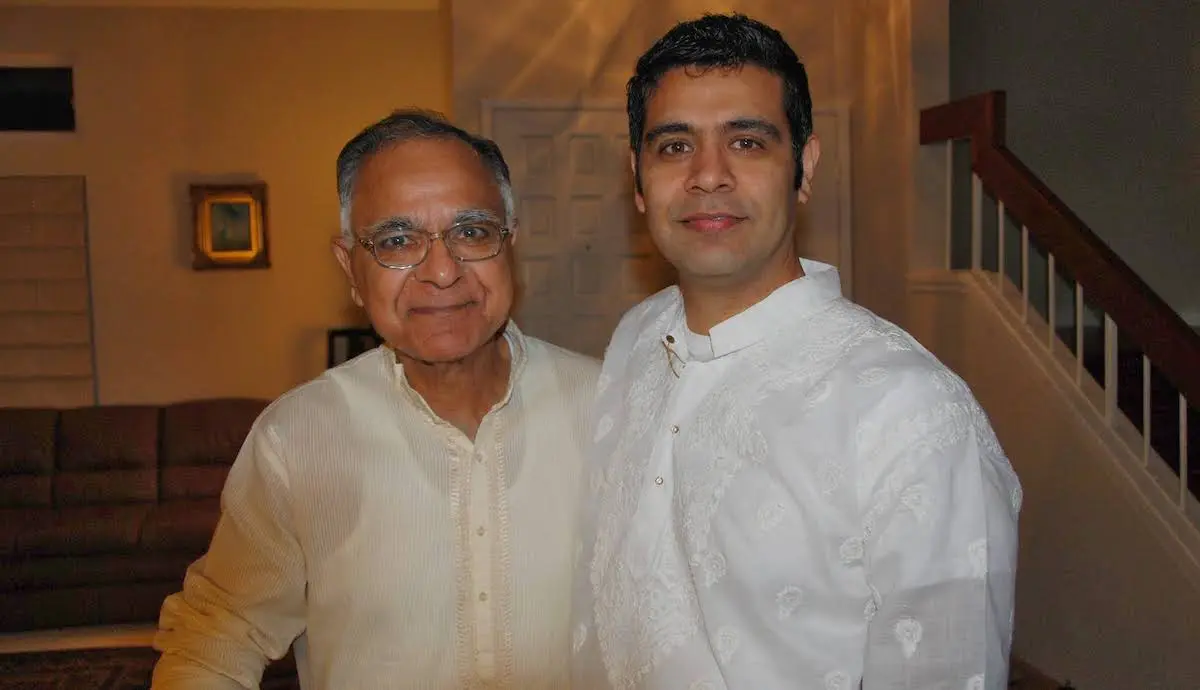

For Ajay Khanna, the difficult decision to move his father Virinder Khanna from their Santa Clara home into an assisted living facility happened when Ajay could no longer lift his dad from bed.

“My dad was a big guy, heavy. When you have to lift somebody, even if they’re 130 or 140 pounds, it’s like lifting a dead weight.” After several months of hoisting his father on and off the bed, Ajay said “I kind of gave up. I just could not do it anymore.”

Virinder Khanna came from India to live with his son and family in 2017 after his wife passed away. However, when Ajay invited his dad to stay, he could not have anticipated the long-term care issues that would upend their lives, as Parkinson’s disease and dementia decimated his father’s health.

Caring for parents

In South Asian families like the Khannas, caring for aging parents is a cultural norm. As long as they are fit and able, adult children will rarely place their parents in care homes, shouldering the burden of caregiving themselves.

Ajay’s father had retired after a successful engineering career at an Indian multinational company. Moving to his son’s home was a natural next step.

In South Asian immigrant communities, almost 29% of families live in extended multi-generational households with grandparents and grandkids, according to Pew.

Virinder became a hands-on grandfather to his two young grandsons. “He had no health issues,” said Ajay. “He’d pick the boys up from school, do some cooking.”

Ajay described his father as a man content with his own company: “He was a bit reserved; he didn’t open up with people.” He loved reading or going for long walks, but was not in the least interested in social events at the local Indian Cultural Center.

A difficult diagnosis

Virinder was about 72 years old when he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s. The trouble started with a mild trembling in his hand, says Ajay, but Virinder became prone to falling as his health declined. He needed more supervision.

Two and a half years ago, Ajay heard a big thud from his father’s room: “He was on the floor. We took him to emergency at Washington Hospital.” Miraculously, his father had no concussion or broken bones, but he couldn’t stand up.

Virinder needed physiotherapy to recover from his fall, and was admitted to a rehab facility in Fremont. His three-week stay was extended to three months.

“He was incapable of doing things on his own and needed support and a walker,” said Ajay. Eventually, the rehab center discharged his father. “They told us Dad could not live in a short-term care facility forever. We had to take him back home.” A health aide came to the house on weekdays to assist with caregiving, but on the weekends, “I was the person doing everything.”

The toll on health

The physical aspects of caregiving soon began to take a toll on Ajay, who is now 51.

“I threw out my back,” he explained. “Dad needed care 24/7. He could not control his bowel movements. He needed to go to the bathroom three or four times a day. Diapers changed. It was continuous. We kept on hearing calls from his room.”

As the disease progressed, so did the number of doctor’s visits.

“There were cardiologist visits, neurologist visits, and then his normal visits,” Ajay explained. “There were always blood tests, scheduled MRIs, and some kind of test happening. He needed to go to the hospital almost every week. If you are the caregiver, then you’re going to the doctor every week, often multiple times. The pressure starts building. We were managing on our own through this time.”

A cry for help

Both Ajay and his wife worked full-time in the tech industry, and found it challenging to fit their schedules around Virinder’s medical appointments.

“We had to take time off frequently. It started becoming a little bit overwhelming for us. We were kind of crying for help,” Ajay said. Eventually, they reached out to a nonprofit organization for assistance. “We told them we were in trouble. We could not take off every other day to take my dad to the doctor.”

The nonprofit’s OnLok PACE program was like “a blessing from heaven,” he continued.

The staff would pick up his father from home and take him to his doctor and physiotherapist appointments; they even provided food assistance when required. When Ajay and his wife needed to travel they provided full accommodation for his dad at their facility.

“That’s when things started to open up for us,” said Ajay. At that point, he and his wife had not had a vacation for several years.

A tough decision

By late 2022, the combination of Parkinson’s and dementia had taken a severe toll on his father’s health. Virinder got progressively worse.

“He kind of lost control,” saaid Ajay. “He needed full-time care. Towards the last six or seven months, my dad could not even move. He began having memory issues and hallucinations.”

Virinder began imagining people in the room though nobody was there, or he would talk about going to his office. “It was not like losing his mind,” his son continued. “It just felt like his mind was someplace else.”

His father’s deteriorating health made it impossible for Ajay to look after him at home. He made the wrenching decision to place Virinder in an assisted living facility.

While searching for care homes, Ajay did not reach out to the Indian American community for advice, explaining “I know sometimes our community is uncomfortable” discussing medical conditions, especially cognitive impairment issues like dementia which are often stigmatized.

He also found it difficult to find trained caregivers or settings that could provide culturally congruent care.

A caregiver crisis

The trained caregiver shortage that the Khannas encountered in Santa Clara County reflects what’s happening across the country.

As its older population increases, America faces a looming caregiver shortage. Santa Clara County is a microcosm of the national caregiving crisis.

Santa Clara County is predicted to have the highest growth in its older adult population, with 18% of its 1.9 million residents over 60, an age group expected to triple to one million by 2030. One of the County’s largest ethnic groups is South Asian (37.4%), according to the U.S. Census.

As this ethnically diverse aging population grows, so will the demand for culturally competent services to address their growing healthcare needs.

California is taking steps to address the caregiver crisis through CalGrows, a comprehensive online training program with incentives designed to empower a network of trained caregivers who can support seniors in the state.

But for families seeking caregiver services for an aging parent, navigating the MediCal system and the In Home Support Services (IHSS) network is an arduous task.

Undeterred, Ajay Khanna said he patiently spent hours with Santa Clara County’s social services department to determine his father’s eligibility for assisted living and how to pay for it.

The information is there if you look for it, said Ajay, who found some answers to his predicament.

End-of-life issues

“At the first location where my dad was placed, I had to contribute around $1,000 a month for his room, which is nothing actually, because the cost is around five or six thousand dollars,” said Ajay. “I think MediCal just took over. They said you don’t have to worry about it. Afterward, that portion was taken care of by Social Security. So, towards his last six, seven months, I didn’t pay anything.”

Ajay added that he was grateful for the care his dad received at the nursing home: “When you’re looking after someone who has Parkinson’s, or dementia, you need to have some skills and training. If dad was at home, he would have had bed sores, because I could not move him. He had a special bed at the care home. They would turn him over every two hours.”

More importantly, continued Ajay, his search prepared him and his family for the end-of-life issues they’d have to contend with in Virinder’s last days. He said that these are issues that the desi community doesn’t really think about or plan for out of respect for living elders.

The nursing home that admitted Virinder asked Ajay on the first day about plans for his father’s end-of-life choices.

“They asked us, ‘Do you want him to be intubated? Do you want him to be force-fed?’” and helped the family make decisions about tough questions like signing a DNR form, and funeral plans, added Ajay.

They were able to pick the pandit (priest), puja (service), and permits for the final rites.

“It’s a pretty morbid thing to do when your dad is still alive, but you need to do that,” said Ajay. “My dad had an amazing life. If he was still in India when he became ill, it would have been more difficult — we could not have cared for him. I feel fortunate that he was with us. That was a huge blessing in itself.”

Ajay’s father passed away in February this year. He was 79.

This article was written with support from the EMS – CalGrows Fellowship Program.

The fellowship aims to spotlight and celebrate home health care providers as essential — unsung heroes — to the health and wellbeing/quality of life of older adults and people with disabilities, a population that represents out of four Californians as of 2030.

If you are interested in becoming a professional caregiver in California, the backbone of California health care, to earn up to $6,000 for learning and using new skills. However, time is running out for caregivers to sign up, as the program ends in August. Caregivers can sign up for the program online at calgrows.org, by phone at (888) 991-7234 or by email at [email protected].