As older and disabled Californians grow more diverse, high-tech caregiving can’t meet them where they are unless it’s also high-touch. Fijian Americans, who comprise a major segment of caregivers, are using their culture to fill this urgent demand.

That’s what Dr. VJ Periyakoil, associate dean of research at Stanford Medicine, told a room of about 30 Fijian graduates of LEADER, a first-of-its-kind program run by her through the Stanford SAGE Lab giving health workers practical skills to care for elderly and disabled people in their preferred language and cultural context.

“But what I learned most wasn’t this or that skill, but that any form of care cannot be stagnant,” said LEADER graduate Lusia Barciet about the training, which can span between four and 12 weeks in-person or online.

“When you care for someone, their needs change the more they age or suffer,” she explained. “How you help them keep from falling, what they need to fall asleep, their nutrition needs, how you can keep them talking so their brain is social and active — this all changes from day to day.”

Barciet and her husband Aseri Rika are live-in caregivers for an 82 year old French man in Sacramento, before which she cared for community members “ages 84 to 94, one or two at a time”.

75% of Fijian Americans live in California, with many in Sacramento. Nationwide, the Census American Community Survey 2015-2019 reports a Fijian immigrant population of 47,000.

“Barciet helps him with physical daily tasks and care including a catheter, while I help him with projects around the house, of which he has so many — right now I’m helping him build a gate,” said Rika.

“He has the mental ability of a man in his 20s, and still thinks he’s in a 20 year old’s body,” he added. “As with stories of people who fall apart as soon as they retire, we’ve both learned how important to care is helping keep the fire alive in his belly, helping him live so he can often have joy.”

Before moving to Sacramento three years ago, Barciet worked as director of human resources at Fiji Marriott Resort, while Rika was a project officer at Fiji Community Development Program.

Fijian care agencies are relatively abundant in California, with three in Sacramento alone.

However, “I’ve only used an agency once,” said Barciet. “It’s so crucial to focus on training us, the caregivers, because we’re so communal. I really work through personal referrals, not agencies. If a child’s parents pass, for example, they refer me to someone else who needs care.”

Among Pacific Islanders in California overall, including native Hawaiians, 26% provide care to friends or family members — the same as white and more than Hispanic and Asian Californians.

In a testament to the strengths of their culture of communal caregiving, Pacific Islanders rank dramatically below all other races and ethnicities for reported financial stress or physical and mental stress due to caregiving. 16.86% of Pacific Islanders report financial stress compared to 56.32% of whites, for example, and 5% of Pacific Islanders report physical or mental stress compared to 16% of whites.

Despite a major dearth of linguistically and culturally specific care training programs like LEADER, language and cultural barriers are often the largest obstacles to care apart from physical difficulties, said Stanford Medicine Dean Dr. Lloyd Miner at the graduation event. “You are often the only ones who can meet them where they are.”

Nearly 6 million Californians, or 15% of the state’s population, were aged 65 and older as of 2021 according to the U.S. Census — a number projected to grow to over 8.7 million, or 20% of the state, by 2030.

The CDC reports that over 7.6 million Californians have a disability.

Caregivers “are truly the backbone of our health care system,” said Connie Nakano, assistant director of the California Department of Aging (CDA), at the Wednesday, July 31 event at the Stanford School of Medicine. To support California’s aging and disabled population, she added, “your commitment is crucial. It makes a difference in countless lives every single day.”

Since it was founded in 2016, LEADER has trained over 650 direct care workers — including home health aides, community health workers, certified nurse assistants and promotores — through funding by agencies including CDA, the National Institutes of Health and the Health Resources and Services Administration.

Nakano pointed to CDA’s own expansive CalGROWS training program as another opportunity for home health workers to earn up to $6,000 for learning and using new caregiver skills. However, time is running out for caregivers to sign up to earn money, as the program ends in August.

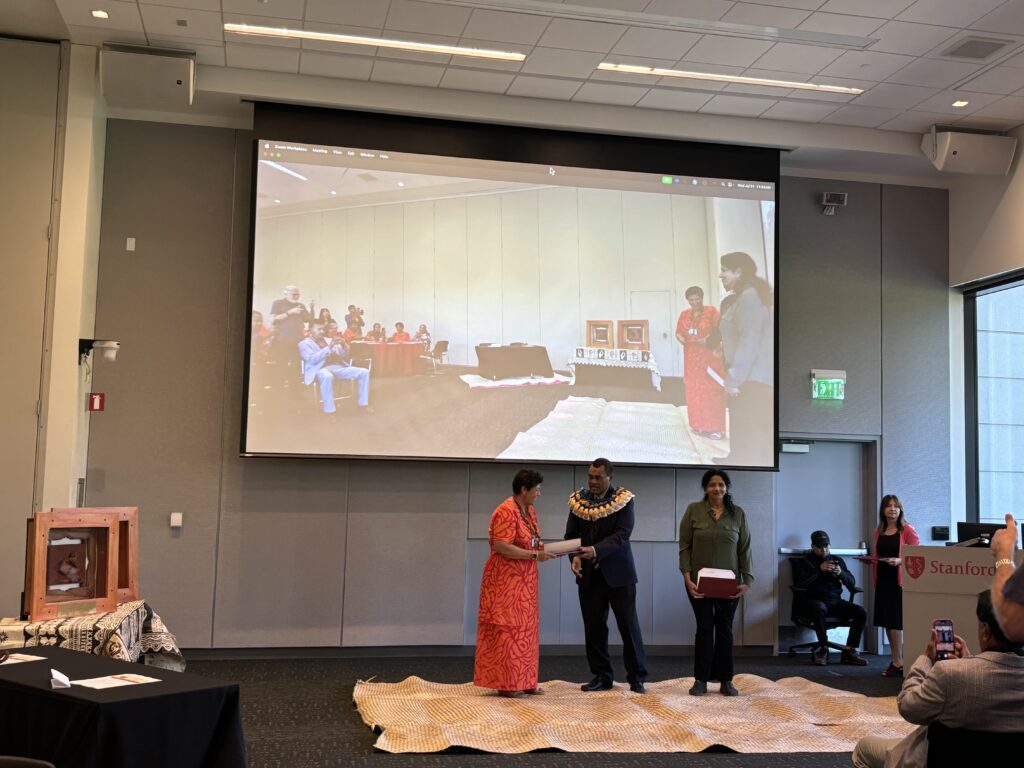

The guest of honor at the commencement, Ratu Ilisoni Vuidreketi — Fijian Ambassador to the U.S. — told the Fijian caregivers “Today we celebrate not only your academic achievements. Not only physical support but compassion, kindness and dignity can be the greatest gift you give to those you serve … May you find fulfillment and purpose in every interaction.”

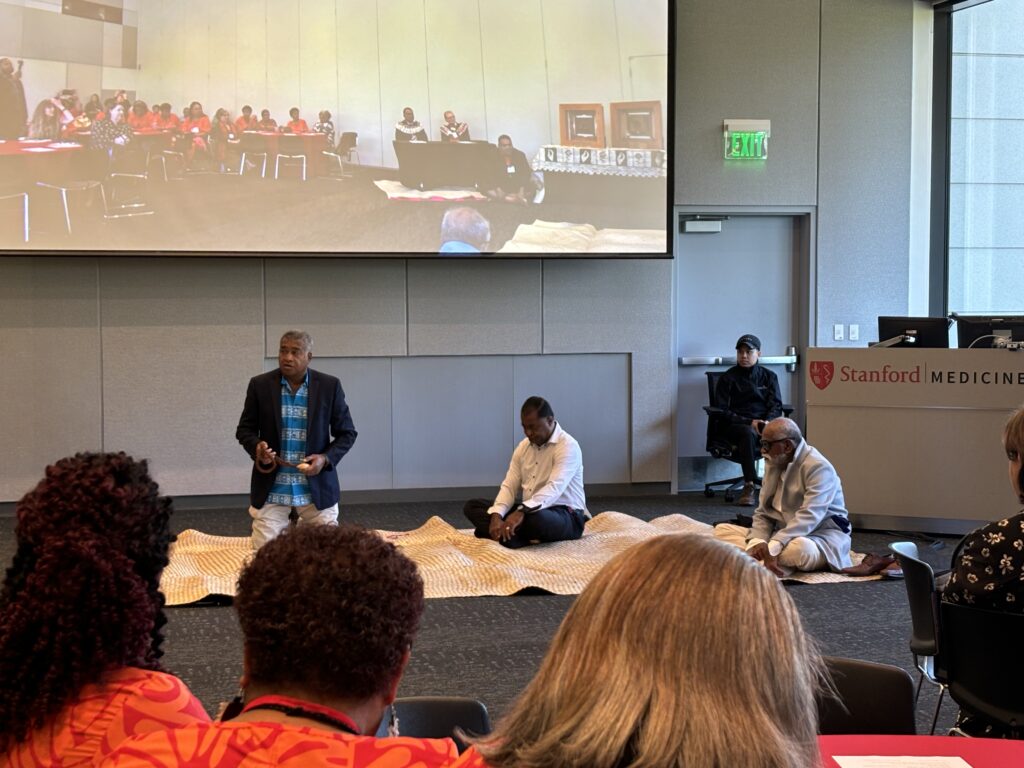

After a traditional Fijian ceremony in the Li Ka Shing Center conference room to honor Vuidreketi and Miner, Periyakoil presented certificates to LEADER graduates, who then convened to sing a traditional hymn.

“Because of our communal culture, the most challenging part of this training was the beginning framework, learning the course of diseases like dementia and how needs change with them,” said Barciet after the event. “For example, in Fiji, there was no dementia. There was no written history. So we are always talking, talking, talking around the dinner table — ‘Remember this person? Remember that place?’ That’s how we live, socially.”

“In Fiji, all our houses were next to each other, so if I’d see someone struggling to wash clothes or build a fire, I’d simply go over and help them, then return to what I was doing,” she added. “We make such good caregivers because caregiving doesn’t even make sense to us as a separate concept. It’s life itself.”