School districts that serve more Black and Latino students, low-income students, as well as English Learners are on average receiving less funding than their whiter and wealthier counterparts. Some states, including California, are bucking the trend.

Those are among the findings of a new study from The Education Trust, which also released a new interactive tool that lets users compare funding across states and individual school districts.

“What the research shows is that significant additional funding for underserved students is required to see the changes in achievement that we would want to see,” said The Education Trust’s Director for P-12 Data and Analytics, Ivy Morgan, who authored the study, Equal Is Not Good Enough.

Morgan spoke during a Dec. 6 media briefing highlighting the data, which looks at state and local funding in school districts across the country along three separate tracks: districts with higher numbers of Black and Latino students, higher poverty districts, and districts serving larger numbers of English Language Learners.

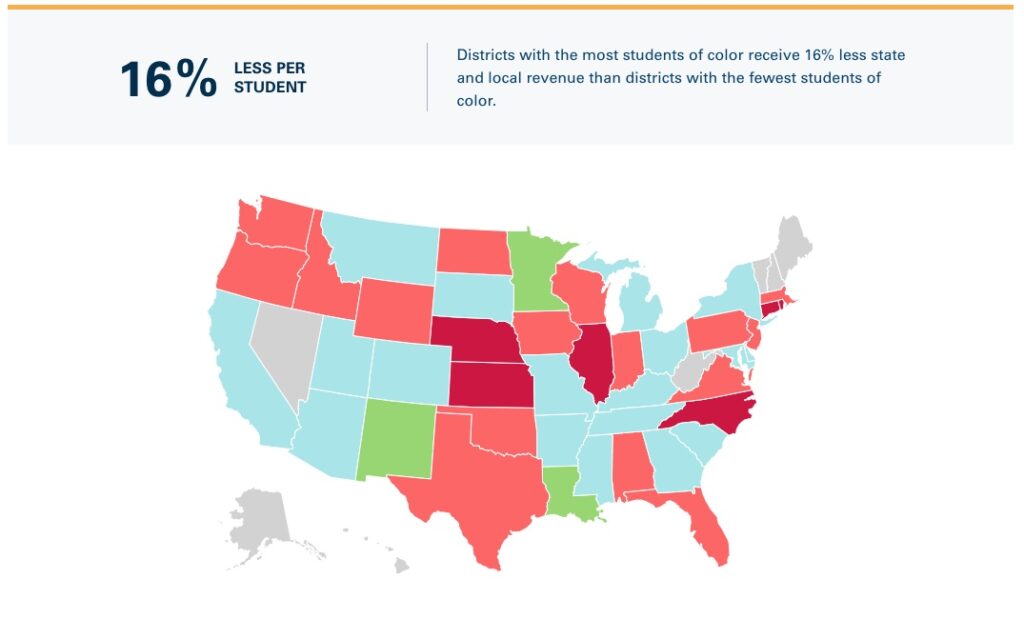

The study updates an earlier report from 2018. Among the findings are that schools with higher numbers of Black and Latino students on average receive 16% less than schools with fewer students in either of these two demographics. “That’s about $2,700 less per student — and in a district with 5,000 students, that gap could mean $13.5 million in missing resources,” the study notes.

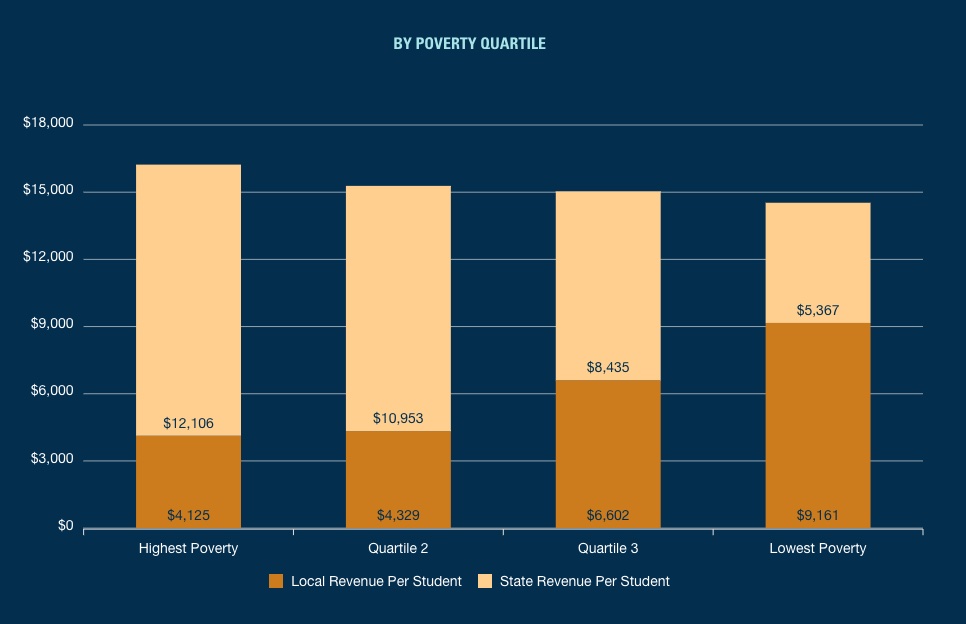

Schools with more English Learners get on average 14% less while high-poverty schools see a gap of about 5% — or about $800 less than what wealthier districts receive.

While funding formulas vary from one state to another, many rely on property values as a key mechanism. Districts with higher housing costs are typically able to raise far more in local funding. The study cites this as one example of how racist housing policies continue to impact communities of color, limiting their capacity to accrue wealth and see greater educational attainment.

State funding, meanwhile, which is based on enrollment numbers and is typically weighted to inflate percentages for higher-need students, more often than not fails to make up for the shortfall.

And while federal COVID relief dollars to the tune of some $200 billion – doled out via Tile 1 regulations, prioritizing high-need districts – helped close the gap, those monies will eventually run out, leaving districts facing a “fiscal cliff” that could exacerbate existing inequities.

Why school funding matters

Smaller class sizes, more experienced teachers, greater resources for student counseling and AP coursework; these are among the advantages that come with more school funding.

“Black and Latino students enjoy science, technology, engineering and math courses and aspire to go to college and pursue careers in STEM fields,” the study notes, “but they are routinely denied access to relevant course opportunities such as AP Biology, AP Physics, and AP Chemistry.”

Fairer funding models would help address this challenge, Morgan says.

They would also lead to more dramatic educational outcomes, including “a whole grade level acceleration of learning,” according to Rucker Johnson, professor of Public Policy at the University of California, Berkeley.

Johnson testified on the importance of equity in school funding during a January hearing in Pennsylvania, among the states with the widest gaps in funding between wealthy and low-income districts. The case centered on arguments by Republican lawmakers that sought to separate questions of funding equity from educational outcomes.

In his testimony, Johnson drew on a 2016 study he co-authored looking at the longitudinal effects of school finance reform from the 1970s to the 1990s on individual student achievement. Among his findings were “eight to 12 months of learning gains” for students in districts with greater funding equity.

But Johnson stressed that funding equity needs to be consistent and predictable to allow districts to put in place the long-term, structural resources necessary to ensure improved outcomes for students.

States that are narrowing the gap

Louis Freedberg is the former Executive Director for EdSource, which reports on education issues in California. “What the Ed Trust report tells me, and this is significant, is that the Local Control Funding Formula really has made a difference in equalizing spending in California.”

Passed in 2014, LCFF injected some $18 billion in spending to the state’s public schools, at the same time reshaping how the state determined how much each district receives, looking at factors including student demographics and poverty rates.

“The state’s highest poverty districts now receive 126% percent more per student than the lowest poverty districts, and districts with the highest percentage of students of color receive 92% more. Just amazing. That is all LCFF,” said Freedberg.

California has since the 1970s prohibited the use of property taxes in school funding.

But Freedberg says what the study fails to show is how districts like Los Angeles — the nation’s second largest after New York, with close to 5 million students — are coping with funding decreases following enrollment declines post-Covid. He also stresses that money alone won’t solve the issue, suggesting that greater transparency in district spending would ensure more effective use of available resources.

Other states have also come farther along in closing funding gaps. The study highlights two, Maryland and Massachusetts, for putting in place funding schemes that on paper would provide close to double the amount for districts with larger numbers of Black and Latino students.

Six states, meanwhile, (Connecticut, Illinois, Kansas, Nebraska, North Carolina, Rhode Island) were cited as providing between 10% and 22% less funding to these districts.

There are also a number of states where funding models approach equity in some but not all categories. New Mexico, for example, offers slightly more per-student spending for high-poverty districts and those with more Black and Latino students but less for districts with large numbers of English Learners.

The study offers policy recommendations that include things like caps on the amount that wealthier districts can raise, as well as formulas that prioritize student need.

“This is about getting the information out there so we can start having more nuanced conversations about inequities in school funding across schools and within districts,” Morgan said, stressing that even in states where there is more parity in funding, given the higher needs among these groups, “equal funding… is not good enough.”