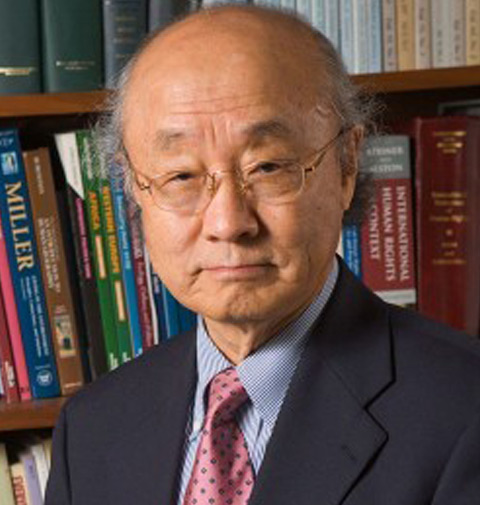

Protests continue in South Korea more than a week after the country’s embattled president, Yoon Suk Yeol declared and then repealed martial law all within the span of just six hours. Since then, thousands of South Koreans have rallied demanding Yoon’s ouster. On Wednesday, the president’s own party announced it would support plans to impeach Yoon, who delivered a defiant speech the same day defending his actions and refusing to step down. Han S. Park is Professor Emeritus of International Affairs at the University of Georgia near Atlanta. He says the current moment is an opportunity for South Koreans to reconsider the very form and structure of the country’s democratic systems. He spoke with EMS’s Jongwon Lee. (This interview was conducted in Korean. It has been edited here for length and clarity.)

What was your initial reaction when you heard the news that President Yoon had declared martial law?

It was not a declaration of martial law. It was an insurrection by the president, not unlike what we saw in 1960 under then-President Syngman Rhee, who sought to concentrate constitutional powers. Then, as today, Koreans protested peacefully. I was part of those protests. We successfully drove Rhee from office. He eventually fled the country, and later died in the United States.

Do you believe Yoon will similarly be driven from power?

Yoon’s government is not going to last very long for various, legitimate reasons. The president abused his presidential power, which is already considerable. But this is just the tail end of a long string of signals suggesting a deep corruption within his government. And South Koreans are fed up, so tens of thousands have come out into the freezing cold to join in candlelight demonstrations. President Yoon will not finish his five-year term, of which two-and-a-half years remain. That’s not going to happen. And it is important to note that this kind of regime change, historically, is not common. It is very unique.

What makes events in South Korea so unique?

If we consider the forms of democracy, there are broadly two models, the American model and the European model. The latter is based on limiting presidential power. The United States, on the other hand, operates on the principle of participatory democracy, which suggests that as long as people participate in producing the power, the power itself is legitimate. Its size is irrelevant.

South Korea embraced the American model without considering the enormous power it leaves in the hands of one figure, the president. And when someone like Yoon is elected, a career prosecutor, with no experience in government or politics, that inexperience is part of what led to a tenure defined by power grabs of all kinds. When power is concentrated in one person rather than institutionalized, it becomes corrupt.

But what we are seeing now in Korea is not the American version of democracy or the European version. It is in some ways closer to what we see in Ancient Greece, a sort of rule by the people, by consensus. It is like a family, where social mores rather than sheer military or political strength hold sway. I think this is quite important. As people turn out to protest and to demand Yoon’s departure, we are seeing a new form of politics emerge.

You mention consensus, yet South Korean politics are notoriously divisive, with liberals and conservatives rarely seeing eye to eye.

Terms like conservative or liberal, these are ideas that took shape in and are tied to European and American forms of democracy, which are both now struggling with all sorts of internal challenges and contradictions. In the United States, conservative is equated with capitalism and often inequality in terms of the distribution of wealth and power. That is the system that South Korea embraced, and the results are clear, with wealth inequality at extremely high levels. On the other hand, in South Korea, if you express any sympathies toward North Korea, you are by default a liberal. The socialism that exists in North Korea is ideally meant to prioritize equality. The form of liberal democracy in South Korea stresses liberty. The two don’t easily go hand in hand. Liberalism falls short when it comes to equality, while socialism does a poor job of promoting liberty. This current moment offers Koreans a chance to consider something new, something that can possibly bring these two ideas – of liberty and equality – closer together.

Professor Han S. Park is Professor Emeritus of International Affairs at the University of Georgia. He previously worked with the U.S. Department of State undeP former president Jimmy Carter. He is the former director of the Center for the Study of Global Issues at the University of Georgia.