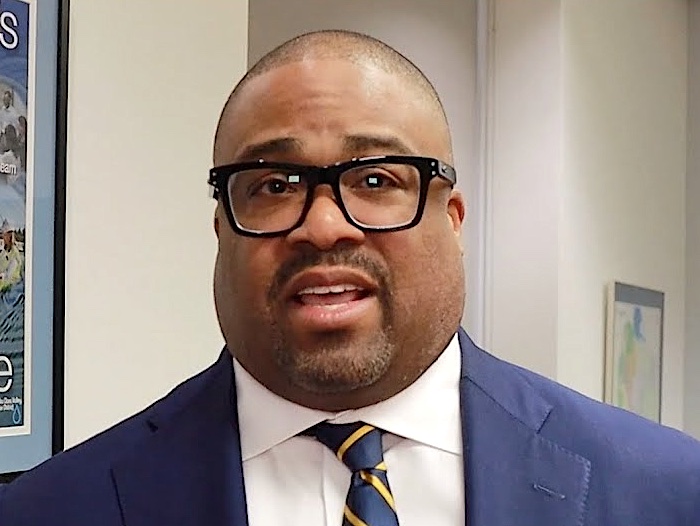

Steve Eaton is still troubled by what happened to him on the last day of March as he drove down an unmarked residential street in the part of old Chico known as The Avenues.

When he was pulled over by a Chico police officer, he remembers telling himself to stay calm and be polite. Surely whatever problem there was would be resolved quickly. But Eaton says his California driver’s license and an obliging attitude didn’t satisfy Officer Juan Valencia, who contended from the start that the 44-year-old African American man had been driving “erratically.”

Eaton was baffled, and told the officer, “It’s beginning to seem like you’re racially profiling me.” And from there the interaction went downhill — rapidly.

Eaton suffers from severe asthma and as the questioning went on, felt increasingly anxious. He asked for medical help as his heart raced and he became short of breath. By the end of the encounter he had collapsed to the ground shaking as he pumped his asthma inhaler and again asked for paramedics. One of two other officers who arrived at the scene called emergency medical services (EMS), Eaton said.

Eaton, who moved to Chico from the northeastern United States eight months ago, believes he was pulled over after Valencia spotted an African American man in the driver’s seat of his Mitsubishi Outlander van. But he’s more upset that Valencia refused to call for help when Eaton told him he had breathing difficulty and needed an ambulance.

“This is definitely about racial profiling,” Eaton said, “but more so, my vitals were at a critical level to the point where I collapsed. That’s not how we want to be policed.”

Chico Police Chief Billy Aldridge did not respond to either phone or email requests for comment on the incident, or on racial profiling in general. The City denied a public records request submitted by ChicoSol for the incident report and body camera video, citing sections of code that exempt many law enforcement records from disclosure requirements. Eaton provided his copy of the police report.

The City also denied Eaton’s request for the officer’s video, telling him the incident is the subject of an internal affairs investigation and the records would be available only by court subpoena.

A one-page report by EMS shows Eaton’s heart rate at up to 140 beats per minute and his blood pressure at a worrisome 174/96.

The police report, authored by Valencia, shows the officer pulled Eaton over at 7:37 p.m. “I advised Eaton I pulled him over due to him driving his vehicle towards the oncoming lane towards my vehicle on E. Sacramento Ave. although not clearly marked on the road separating the lanes.”

Eaton said he was out looking at neighborhoods — and driving cautiously because this one was residential — when the officer passed him, then made a U-turn and followed him as he turned left on Palm Avenue. The police report says Eaton slowed down to “well below 25 MPH …”.

After Eaton made the racial profiling comment, he said the officer sniffed at the open window. Valencia then said he smelled alcohol and ordered Eaton to take a field sobriety test. But by then, Eaton said, he was scared and unstable, and asked for a breathalyzer instead. That test showed there was .0% alcohol in his system.

“While instructing Eaton on the walk and turn he would not follow directions,” the police report states in relation to Valencia’s attempt to conduct a field sobriety test, “and claimed he was unable to breath (sic) and kept asking for a supervisor.”

Eaton said that when he asked for medical help, Valencia said, “I’m not calling EMS.”

“I said, ‘Please call EMS.’ I started praying and collapsed to the ground,’” Eaton said. “I could forgive all actions -– even though maybe I shouldn’t -– until he refused to call paramedics while I was on the ground pumping my asthma pump.”

Eaton said Valencia was soon joined by two more officers, Chris Sullivan and Nicolo DiStefano. One of the two suggested Eaton needed medical help and called paramedics, Eaton says.

Eaton wasn’t cited for any offense as a result of the encounter.

The police report provided by Eaton leaves blank the space where race should be entered. Chico police are required by state law to track the perceived race of everyone who is stopped.

RIPA requires race data reporting

California’s Racial Identity and Profiling Act (RIPA), passed in 2015, prohibits racial and other types of profiling and requires that law enforcement agencies collect “perceived” demographic data, including race, and report that data to the state’s Department of Justice (DOJ).

The Act was passed as part of an effort to get a handle on racial profiling in California driven by conscious or unconscious bias. When the Act passed, there was already a wealth of evidence that racial profiling was a problem affecting the relationships between communities of color and law enforcement agencies. But the organizations that sponsored the legislation wanted statistics that would show, in a concrete and undebatable fashion, what was happening and track any progress that is made.

One of the organizations at the table was the California Hawaii NAACP State Conference.

“Data rules the day,” said Rick Callender, president of the California Hawaii NAACP and a former two-term student body president at Chico State (1992-1994.) Callender helped conceptualize the RIPA legislation back in 2014. “If you have the data, you can see who’s stopped, who’s searched and who’s made to curb sit.”

The latest RIPA report, for the year 2021, shows that Latinx people were the largest percentage of some 3 million law enforcement stops in the state as a whole. African Americans were the most likely to be stopped because of “reasonable suspicion” they were engaged in criminal activity. Black youth were searched at nearly six times the rate of white youth, the report says.

Black individuals had the highest rate of being detained curbside or in a patrol car. Yet, Blacks stopped by law enforcement had the lowest proportion of traffic violations of the stops, and made up the greatest proportion of stops that concluded without any kind of charge or citation.

Chico Police Department referred ChicoSol to DOJ for 2022 RIPA data, which it said it began providing in January of this year. (The deadline for data delivery for small departments was April 1, 2023.)

The Chico State University Police Department submitted data for 2021 that gives a picture of who was stopped that year by that agency. Data posted online by DOJ shows that African Americans were believed by the officers to comprise almost 7 percent of the total number of their stops.

African Americans make up less than 3% of the student body at Chico State and the population of Chico.

Eaton: A case study

Eaton has spent most of his life in majority-white communities and calls the encounter with Valencia “really traumatic.”

“Nothing like this has happened before,” he said. “I’ve never been treated like this before, never.”

Eaton says his move to Chico -– due to an affiliation with Chico State University -– has proved more difficult because of the incident. “We all want to feel safe, and it depends so much on the actions of police.”

After checking his vital signs that night, paramedics offered to take Eaton to Enloe. Eaton declined and later went to the ER on his own.

He filed a complaint with the City and is awaiting a response.

RIPA says civilian complaints can serve as “an effective law enforcement accountability measure.” The Advisory Board says complaints can help prevent misconduct by turning up problems in policing practices early, and notes that racial profiling in particular can trigger “stress responses, depressive symptoms, anxiety …”

Eaton says he’d like two things: An apology and an effort to upgrade racial bias training. His encounter with Chico police, Eaton said, could be a “case study in how we can better police.”

Leslie Layton is a freelance journalist and the editor of ChicoSol, where this story first appeared.

This resource is supported in whole or in part by funding provided by the State of California, administered by the California State Library in partnership with the California Department of Social Services and the California Commission on Asian and Pacific Islander American Affairs as part of the Stop the Hate program. To report a hate incident or hate crime and get support, go to CA vs Hate.