What should the government look like? And how much should it cost? These two basic questions will be front and center as President-elect Donald J. Trump, Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy lead a new initiative, the Department of Government Efficiency. Their goal is a trimmer, cheaper federal bureaucracy by July 4, 2026.

Musk has said his goal is to reduce the number of federal agencies to less than 100 – a reduction from 400-plus now. Congress would have to agree in most cases.

The idea of government reform is seductive – and has a long history.

Two centuries ago in 1824, the Bureau of Indian Affairs was created with the hope that a new agency could do better. Congress wasn’t moving. And the Secretary of War John Calhoun was tired of waiting, so he used a routine vacancy to appoint Thomas L. McKenney as the commissioner of Indian affairs. It was almost a decade later before the structure of the commissioner was authorized by Congress. The Department of Interior was created in 1849 and the Bureau of Indian Affairs transferred. Only thing. Not much changed in terms of reinvention or policy direction.

“The old attitudes of the War Department days and the new worldview of Interior combined to produce within the Bureau of Indian Affairs a broad conception of its mission. It was to regard Indians as increments upon the land without any ultimate right to existence. Indians were hardly to be trusted, and were generally considered hostile,” wrote Vine Deloria Jr. in “My Brother’s Keeper.”

And that gets to the biggest challenge of any government reinvention: You have to take on significant constituencies that benefit from government. Some of those interests are huge: The 2.3 million federal, civil employees have a stake in any changes and outcomes. A significant reduction in personnel would cause a sharp drop across the economy, especially in rural areas.

Richard Nixon had a grand idea about government reinvention. He wanted four new cabinet agencies: the Departments of Natural Resources; Human Resources; Economic Development and Community Development to work with the State Department, Justice, Treasury and Defense. (Instead there are more than 20 existing federal agencies, including independent agencies.)

My mentor, Forrest Gerard, Blackfeet, who worked for Sen. Henry Jackson, a Democrat from Washington, in the Senate, told me that Congress could never buy into such a plan. Eight agencies meant eight committee chairs, far fewer subcommittee chairs, and less oversight by members of Congress. In order for Nixon’s plan to work, Congress would have to agree to less power.

Will a new Republican majority be willing to give up its own powers?

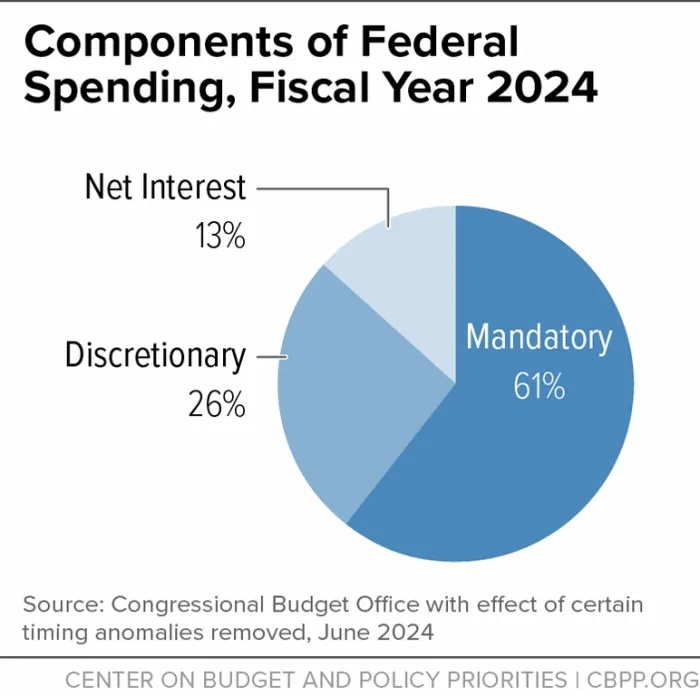

Big Picture: How federal dollars are spent

Of course the administration of programs that impact Indian Country are a tiny fraction of the federal budget. More than 60 percent of the budget goes to “mandatory spending,” or Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid. (The idea is that if people are eligible for the program … the money is there.) Interest on the debt accounts for another 13 percent of the budget, leaving 26 percent for everything else. Nearly half of that last account is money spent on Defense.

The discretionary spending budget for domestic programs is about $919 billion or about 14 percent of all total spending. The price tag for government agencies that serve American Indians and Alaska Natives are about $4.6 billion for Interior and Bureau of Indian Affairs and another $8 billion for the Indian Health Service.

Musk has called for spending cuts at about 30 percent – or $2 trillion. The only way a number that large could be implemented would be deep cuts within mandatory programs – and the easiest political target is Medicaid, health insurance. (Social Security and Medicare serve older Americans, starting at 65 years old for Medicare.)

There are clues about what happens next. Two right-wing think tanks, Heritage and Cato, as well as the House Republican Study Committee, have already outlined parts of the budget that could be cut. Medicaid is a top target.

The House plan would cap Medicaid and children’s health insurance spending with block grants to states. The House says the Affordable Care Act “expanded an already overburdened and ineffective Medicaid system, bringing public health care spending to 43 percent of total health care spending in the United States in 2021.

The Kaiser Family Foundation reports these block grants would reduce the federal contribution, so that states would have to either make up the difference or eliminate the programs. A previous Trump administration budget capped Medicaid and proposed spending $1 trillion less over 10 years. “More recent Republican proposals, the RSC FY 2025 budget and Project 2025, call for capped Medicaid spending as well as a match rate of 50% for all eligibility groups and services or a ‘blended’ match rate.”

Two-thirds of all Americans have a connection to Medicaid programs.

The Center for Budget and Policy Priorities, a left-wing think tank, says “nearly 74 million people receive health coverage through Medicaid, so cuts of this magnitude would result in millions losing access to comprehensive coverage.”

A drop in Medicaid could have a dramatic impact on the Indian Health system. If a patient is eligible for Medicaid, then the IHS provider has more access to resources, including life-saving care. (The per patient cost at IHS is about $4,079 compared to $8,109 for those covered by Medicaid insurance.)

There are so many reasons why Medicaid is an essential element in the Indian health system. First, by law, all of the money is spent at the local unit (instead of added to the budget as general revenue). Second, if a person is eligible for Medicaid, the money follows. It does not need an appropriation. If you count children in the equation, funding from Medicaid pays for 1 out of every 4 IHS patients, more than one million patients. And even that understates the impact because in some locations, such as rural Arizona, Medicaid accounts for half of a clinic’s revenue. And Medicaid is essential for urban Indian programs, accounting for 90 percent of the funding stream.

The Kaiser Family Foundation says there remain “persistent disparities in health and health care.” Since the Affordable Care Act was enacted, Medicaid has been a big part of the solution and now more than one in four non-elderly adults and half of children have coverage. In states with Medicaid expansion the number of uninsured American Indians and Alaska Natives fell by twice as much as the rate in non-expansion states.

This is important because insurance dollars – private or public ones such as Medicaid – remain with the health care unit. “Reductions to Medicaid, including loss of the expansion, could result in coverage losses” for Native Americans and reductions in revenue to IHS and tribal providers, limiting access to care” for patients.

Cutting support for food and housing

In the first Trump administration there were four proposals to reduce the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, or Food Stamps) by about 30 percent of $200 billion.

The playbook for SNAP reform is similar to Medicaid. A proposal from another right wing think tank, the American Enterprise Institute, calls for increasing state financial participation in the program by requiring them to fund a larger share (in exchange for fewer regulations).

Similar cuts are proposed for housing assistance, community development block grants, and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families.

Look for more debate about less in the coming weeks. Of course all of the programs that are directed to Indigenous people or tribal nations are such a small section of the federal budget that it’s easy to ignore the implications. That would be a mistake.

The era of termination began as a cost cutting initiative. After World War II Congress was looking for ways to make the government more efficient, and turning over matters related to American Indians fit that bill (even if unconstitutional). When he served in the House, Henry Jackson along with a Republican from South Dakota, Karl Mundt thought the time had come to terminate Indian programs and tribal nation relations.

Jackson said: “We have been appropriating funds for Indian administration at least since 1775, when Benjamin Franklin, Patrick Henry and James Wilson were appointed Indian Commissioners by the Continental Congress. For 170 years the total of our annual appropriations for this purpose has been growing. Today our Indian population is increasing twice as rapidly as our white population. Unless we do something to reach a fair, just, and permanent solution to the Indian problem, that will incorporate the Indian into our national economy, we are going to have to look forward to spending millions every year on Indian administration. That would be the inevitable result of a ‘do- nothing’ policy.”

The idea was to use claims settlements as a fund and done measure because, as Jackson said, “as long as these claims are pending, the Indians will stay on the reservations and never want to leave, and it simply means more cost to the government, and from an economic standpoint we have come to the conclusion that this is about the only solution.”

In the Senate the main architect of termination was Utah Republican Arthur Watkins. His brand of anti-government rhetoric would sound familiar today. He used every tool available to promote his termination policies. So much so that Phileo Nash, then Wisconsin’s lieutenant governor dubbed the process “involuntary termination” because tribes had so little say. Watkins dismissed the promises made in treaties. He said Indians “want all the benefits of the things we have – highways, schools, hospitals, everything that civilization furnished, but they don’t want to help pay their share of it.”

We now know that termination was a failed policy – even if the only metric is government reform.

A meeting in 1961 of 64 tribes in Chicago included a Declaration of Indian Purpose that set out self-determination as the only appropriate policy. “The basic principle involves the desire on the part of Indians to participate in developing their own programs with help and guidance as needed and requested, from a local decentralized technical and administrative staff, preferably located conveniently to the people it serves. The Indians as responsible individual citizens, as responsible tribal representatives, and as responsible Tribal Councils want to participate, want to contribute to their own personal and tribal improvements and want to cooperate with their Government on how best to solve the many problems in a businesslike, efficient, and economical manner as rapidly as possible,” the declaration said.

One other “reform” worth mentioning is a plan in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations to move Indian programs out of the Interior Department and into the Department of Health, Education and Welfare. This was an idea that followed termination – and died because of tribal and congressional opposition. Two task forces in 1966 and 1967 proposed a limited transfer, Indian education, while a more outrageous proposal to include most of the agency’s functions. But members of Congress – especially those on Interior-related committees – had zero interest in losing their say over federal programs. And at a meeting with tribal leaders the Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare John Gardner tried to make the case that the shift would be seamless. He promised that treaty rights would be secure. Tribal leaders would still have access to top agency leadership. The response? One tribal leader said: “Why, if there are to be no changes at all, do you want to transfer the Bureau to HEW?”

That reform did not happen. And it wasn’t the only time: More than one administration had the bright idea to move all Indian education departments out of the Bureau of Indian Affairs into the Department of Education. A combination of tribal leadership and congressional opposition doomed every attempt.

The federal government only directly operates two school systems, those in the Department of Defense and the 183 schools, serving 46,000 students, run by the Bureau of Indian Education in the Interior Department. More than 90 percent of all Indigenous students attend public or private schools outside of the BIE.

The Department of Education will be a target in the Musk-Ramaswamy plan. “President Trump’s talked extensively about areas like the Department of Education. Obviously, those kinds of agencies shouldn’t even exist and should be returned to the States,” Ramaswamy said on Fox News Sunday. “But it’s a culture that’s pervaded the entire federal government: of hiring people who have no accountability to everyday Americans.”

The key element in this government reinvention is disruption. The Department of Government Efficiency starts with the goal of changing the very nature of the federal government.

“We expect mass reductions. We expect certain agencies to be deleted outright. We expect mass reductions in force in areas of the federal government that are bloated. We expect massive cuts among federal contractors and others who are over billing the federal government,” Ramaswamy said.

And who will be the ones deciding? Hiring for the department is being coordinated on Musk’s X social media platform. “We don’t need more part-time idea generators,” said a recent post. “We need super high-IQ small-government revolutionaries willing to work 80+ hours per week on unglamorous cost-cutting. If that’s you, DM this account with your CV…”

Mark Trahant, Shoshone-Bannock, is editor-at-large for Indian Country Today, where this story first appeared. On Threads and Instagram: @TrahantReports. Trahant is based in Phoenix.