New York City has its fair share of legacy papers, though none that are rooted in its diverse communities. The city’s many ethnic media outlets, meanwhile, tend to write for the communities they serve.

Which is what makes the non-profit news site Documented so unique, combining as it does local journalism with a service-oriented philosophy targeting New York’s expansive immigrant population.

“What Documented does is it builds bridges throughout those communities and reports the totality of those communities,” says Amir Khafagy, who covers labor issues for the paper. “We try to find issues that will have a lot of overlap, and there often is a lot of overlap.”

Founded in 2018 by Max Siegelbaum and Mazin Sidahmed, the idea for Documented goes back to when both worked as reporters in the Middle East. Siegelbaum was drawn to migration, especially during the Syrian Civil War, while Sidahmed became interested in issues of migration and national security. Both felt that a local, boots-on-the-ground perspective covering these topics was missing from U.S. media.

“We always tried to figure out how to work together on this subject,” recalled Siegelbaum. “It is so big, and important, and complex. And there were so many ways that it affected our lives, but we felt like it was being covered piecemeal.”

The pair eventually returned to the U.S. and studied together at Columbia Journalism School. As they refined their pitch for Documented, they drew on their experience as reporters in the Middle East. Stories written for a foreign, English-language audience, they observed, tended to disappear into the news cycle.

“You would write a story about a Syrian refugee or something, and then it would be published, and then it would just be gone,” says Siegelbaum. Local news, he points out, is “completely different”— far more sustainable, and beneficial to the communities it serves.

“This is where we live. This is where we cover. And this is our community. We had to make a concerted effort to at least have that audience—immigrants in NY—given the opportunity to see the work.”

‘Service journalism’

While Documented does its share of “traditional journalism:” breaking news or investigative reporting, for example, its central ethos, according to Siegelbaum, is “service journalism,” engaging directly with immigrants, and providing the resources they need to navigate life in the U.S.

When journalist Nicolás Ríos, Documented’s Audience and Community Director, conducted research on the Spanish-speaking Latino community, he found a clear disconnect between the news cycle and what people in the community look for in coverage.

“We found that there was a need for information that could be useful for people in their everyday lives,” said Ríos, who developed a Spanish-language resource using the social media platform WhatsApp that offers answers and information on concrete necessities – legal, health, education – to residents.

When COVID-19 hit, most of the questions fielded by Ríos tended to focus on where to get Covid tests or PPE equipment. So he began compiling the information into articles, which he then linked on WhatsApp. That later became the foundation for Documented’s current Resource Guide, which contains over 30 articles, covering everything from where to get COVID vaccines to accessing free legal help, renewing DACA, and opening bank accounts.

The WhatsApp group, meanwhile, remains a crucial channel for people needing in-language information on how to apply for H1B1 visa, for instance, or SNAP benefits.

“We could be doing a better job of putting a spotlight on positive things that happen within the immigrant communities of New York,” says Ríos. “But what we’re doing now, very brilliantly, is publishing information that is actually useful to them.”

“It’s not parachute reporting. It’s not someone coming from outside,” says Khafagy, noting that even the paper’s more traditional reporting is often inspired by input from community members and their families. He gives as an example a recent story about a group of migrants who reached out via the Whats App platform.

“They were sending us videos and stuff all the way from Panama, and then we met them when they finally came to New York,” Khafagy recalls. “So, we got a look at the migrant crisis from a perspective never before seen, because we built these relationships in the community.”

On a larger scale, however, the WhatsApp group reflects Documented’s core philosophy: “boots on the ground” reporting that is both centered on an immigrant community’s needs, and written by community members themselves.

Reporting from within

Khafagy, whose mother is Puerto Rican and father Egyptian, grew up in Jackson Heights, Queens and says his personal experience gives him a deeper understanding of the community he covers, including the time he reported on cab drivers demanding debt relief from the city

Khafagy’s own father was a yellow cab driver, and Khafagy recalls going to the NYC’s Taxi and Limousine Commission with him to pay the exorbitant fines often imposed on drivers by local law enforcement.

“My firsthand experience really got me thinking maybe I should really begin to investigate — are these fines excessive, and are they targeting these communities disproportionately,” he recalls. “And it turns out that they were, and we were able to do a story on that.”

Ultimately, Khafagy says his goal is to produce journalism that has a “real time impact” on the communities being covered.

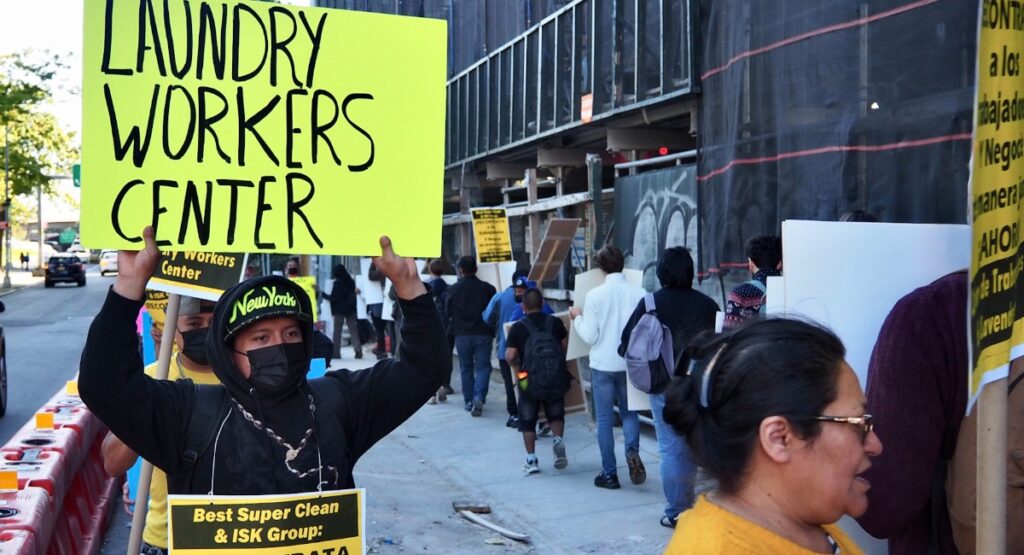

Khafagy’s coverage of unsafe conditions faced by immigrant airport workers was later cited by the National Council of Occupational Safety and Health. An investigative story on how millions of dollars of aid raised after a deadly Bronx fire failed to reach the community lead to mayor Eric Adams disbursing the funds to victims — and then some extra. And a week after Documented published a story on wage theft from immigrant workers at the US Open, the tournament paid the wages. (“They were embarrassed by our story,” Khafagy says.)

Per Khafagy, the key factor to these successes is reporting that operates from within the communities being covered. “Documented is cultivating reporters from these communities themselves, to be able to report on them, because they’re there.”

Traditional journalism ‘with a facelift’

Siegelbaum shrugs off those who derisively describe Documented’s work as advocacy journalism. He prefers the term, “traditional journalism with a facelift.”

“We’re not advocacy journalism. We’re not advocating for any sort of specific change, or we don’t have any kind of political leanings,” he says. “We see what we do as a service that newspapers have engaged with for decades.”

Ríos says the “advocacy” label is often applied to journalists of color providing resources to underserved communities.

“If Bloomberg publishes a guide on how to invest in crypto — that’s not considered service journalism, it’s considered an explainer. It’s not considered advocacy for crypto investors,” he says. “When the question is about money for wealthy people, it’s never advocacy, right?”

Instead, Ríos describes Documented’s data-driven, fact-based work as “pure journalism.”

Khafagy is less bothered by the term. “I’m trying to make an impact that’s going to help positively change people’s day to day lives. And how I do that is by covering stories I think are important to those communities,” says Khafagy. “If that’s advocacy, then that’s what I do.”

The Documented team recently conducted a major study of the Chinese immigrant community, and is now analyzing the data with the goal of providing more relevant services and journalism.

All this work comes amid a slew of media shut downs and layoffs, including the closure of Buzzfeed’s news unit, and lay offs at Vox and the LA Times.

But Siegelbaum is not worried. “I’m hopeful because I feel like there’s a lot of energy and opportunity in this space right now.”

Khafagy is equally optimistic that the publication’s grassroots, service-oriented journalistic approach will continue to be successful.

“We’re a small but growing newsroom,” he says. “We want to serve our communities and make them feel like it’s something that they own, something that’s there.”