Clockwise from top left: Melody Cannon-Cutts, Public Health Program Manager, Del Norte County Department of Health and Human Services; Terry Supahan, Executive Director, Del Norte & Tribal Lands True North Organizing Network; Miguel Pelayo-Zepeda, Del Norte-based community outreach organizer; Thayallen Gensaw, Del Norte high school student; Daphne Corstese-Lambert, Director of Del Norte Mission Possible, Del Norte Senior Center; Khou Vue, teacher and Hmong Cultural Center Board member

Also available in Chinese, Korean, and Spanish.

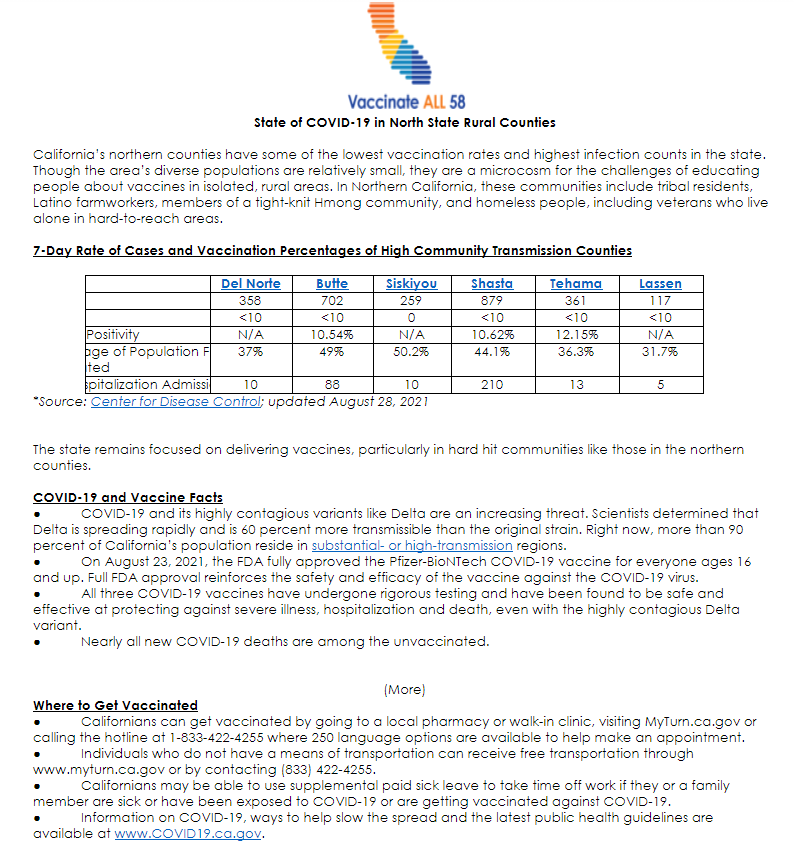

Del Norte county is a microcosm for what it takes to promote vaccines in remote rural regions with limited communications infrastructures.

By: Jenny Manrique

Amid majestic redwood forests, bordering the Pacific coast in the northwest corner of California is the new epicenter of soaring COVID infection rates: Del Norte County.

The spread of the Delta variant has motivated activists to create new strategies for promoting vaccines in a remote rural region with limited communications infrastructures, a single hospital, and low inoculation rates.

“Until very recently, Del Norte experienced low hospitalizations, and while every death is significant, we had experienced only five until April 2021,” said Melody Cannon-Cutts, Public Health Program Manager at Del Norte County Department of Health and Human Services, during a briefing organized by Ethnic Media Services and supported by the Center of the Sierra Health Foundation.

“Following the reopening in the state in June, positive cases have increased from 23 to 90 after the July 4 holiday … Our current positive cases are now at 341. Unfortunately, we have lost 10 residents in the last week,” she added.

Del Norte has a population of around 28,000, 17% of whom are Latino with Mexican roots. The county is home to Crescent City, the county’s only city, and the unincorporated communities of Smith River, Gasquet and Klamath which are served by only one hospital, the Sutter Coast, with 60 beds. 11 of them are ICU beds and are full.

“We began providing the vaccine in December 2020 to healthcare workers and first responders. Then we moved on to the older populations and by April 2021, we were providing 400 vaccines at each vaccine clinic,” Cannon-Cutts continued. “Despite these efforts, fully vaccinated rates are low in comparison to the rest of California: we are currently at 43.6% while the state is around 66%.”

Vaccine hesitancy, mistrust of government and misinformation are rampant, and community organizations are redoubling efforts to demystify vaccine rumors.

According to Miguel Pelayo-Zepeda, a community outreach organizer with Latino farmworkers, who work in the fields of Smith River picking lily bulbs or in the area’s dairy farm, “the reason people are getting vaccinated has changed: they are noticing the community members are dying from COVID.”

Used to gathering at social events such as quinceañeras or town fairs, Latinos are deeply affected by the isolation caused by the virus. For this reason, even though Pelayo hears things like: “the vaccine will make me as sick as the virus”, his strategy is not to criticize, but to foster those social relationships again.

One successful effort was a lunchtime mobile vaccination clinic at Alexandre Dairy Farm, where bilingual nurses and interpreters helped workers overcome their fears. There is also a pop-up clinic at Smith River’s La Jolla deli every Thursday from 10 am to 6 pm which offers vaccines, without the need to show any ID, while Pelayo himself distributes tacos to those who receive the shot.

“We are trying to build the network and we are doing it by building resources for the community…such as ESL classes and immigration clinics.”

Within Native American communities, where vaccination rates are high, doubt persists mainly because of mistrust in the government. “They don’t want or are afraid of dealing with the government at any level, whether it’s local or federal supporting clinics,” said Terry Supahan, Executive Director at Del Norte & Tribal Lands True North Organizing Network, who is a member of the Karuk tribe.

“We continue to try to reach out and talk about risky behavior … we’ve had to cancel many tribal religious ceremonies and spiritual efforts that were in the villages because we do not want to be responsible for bringing loved ones and people who we care about into harm’s way.”

Supahan said that since the very beginning his community have followed social distancing and masking and listened to epidemiologists and scientists. That is why he brings a timely message to the elderly and their extended families: “Adults need to do a better job of protecting children because vaccines are not available to them yet.”

Unhoused

Daphne Corstese-Lambert, Director and Founder of Mission Possible, a project of the Del Norte Senior Center, that serves the rural homeless population, says that unhoused people deal with different disabilities (developmental, physical or health mental health), which has made their access to services even more difficult during the pandemic.

“I’ve tried to help them with the paperwork but they can’t read. When we give them printed information, they’re not getting it and the ones who know how to read a lot of times have such a distrust with the government agency, because during the pandemic everything has been closed down, ”said Corstese-Lambert.

According to her own data, about 700 people are unhoused in the county, 60% of them are seniors and many are veterans, whose records have been lost during the fires in California.

“What Mission Possible has been able to do during the pandemic is relationship-based case management, treating every person as an individual and listening to them … connecting people with agencies that really want to help and promoting vaccination.”

Khou Vue, Hmong Cultural Center Board member in Crescent City, and an elementary school teacher who was born in a refugee camp in Thailand, said that even though his community too has great mistrust of the government, they have taken the pandemic “very seriously.”

“We canceled all sorts of spiritual and religious rituals, funerals and weddings. I still have 14 weddings to go but we have made these sacrifices, because we knew that COVID-19 was real.”

Vue himself lost nine members of his family in a period of two months at the beginning of the year and that is why he is in charge of spreading the message of vaccination through the clans leaders, and what he calls “a tree telephone”.

“At the beginning we activated phones to buy food and shop for the elders who had health issues… Many of our elders do not speak English nor read in any language, not even Hmong. So, communication for us, primarily has to be a phone call or a visit in person.”

To dispel all myths about vaccines, they also show videos about the situation of the pandemic in critical areas of China and India.

Thayallen Gensaw, a 16-year-old Del Norte High School student, member of the Yurok tribe, recently got vaccinated in response to a principle he was raised on: “I always put others before myself, that’s what we do in the tribe: we put the land before ourselves, we do everything for others and for the land.”

Despite being a healthy person and not being concerned about what might happen to him if he gets COVID, he did think about his father who has underlying health conditions.

“Unfortunately, there’s a lot of people my age that care more about themselves; they don’t realize the importance of getting vaccinated because they feel invincible. They don’t know what effects that can have on older people, if they are close to their grandparents, aunties, uncles, their own parents and younger siblings,” Gensaw said.