A stabbing was reported at Franklin High School in Los Angeles on the morning of January 29, 2025. As police vehicles swarmed the school, students at neighboring Academia Avance charter school panicked.

“When they see police, and when they hear helicopters, it is immediately seen as, or thought of as immigration,” says St Claire Adriaan, Community Schools Coordinator at Academia Avance, where 93% of students are Latino, many of them from mixed status families with undocumented relatives.

That sense of fear comes as President Trump implements his campaign of mass deportations, targeting immigrant communities nationwide. Data from the US Department of Homeland Security show 37,660 individuals have been deported during Trump’s first month in office, fewer than the average of 57,000 monthly deportations during the final months of President Biden’s presidency.

Still, officials with the Trump administration say the number of deportations will rise in the coming months as the president looks to expand arrests and removals.

Meanwhile, raids in major cities continue to stoke fear and anxiety as families grapple with the ripple effects of Trump’s war on migrants.

“I saw it firsthand when ICE went to my middle school and they picked up the father of one of my classmates,” says Jair Manuel Solis, who was a student at Academia Avance in 2017 during Trump’s first term. He remembers thinking to himself, “What could have we done to be more prepared?”

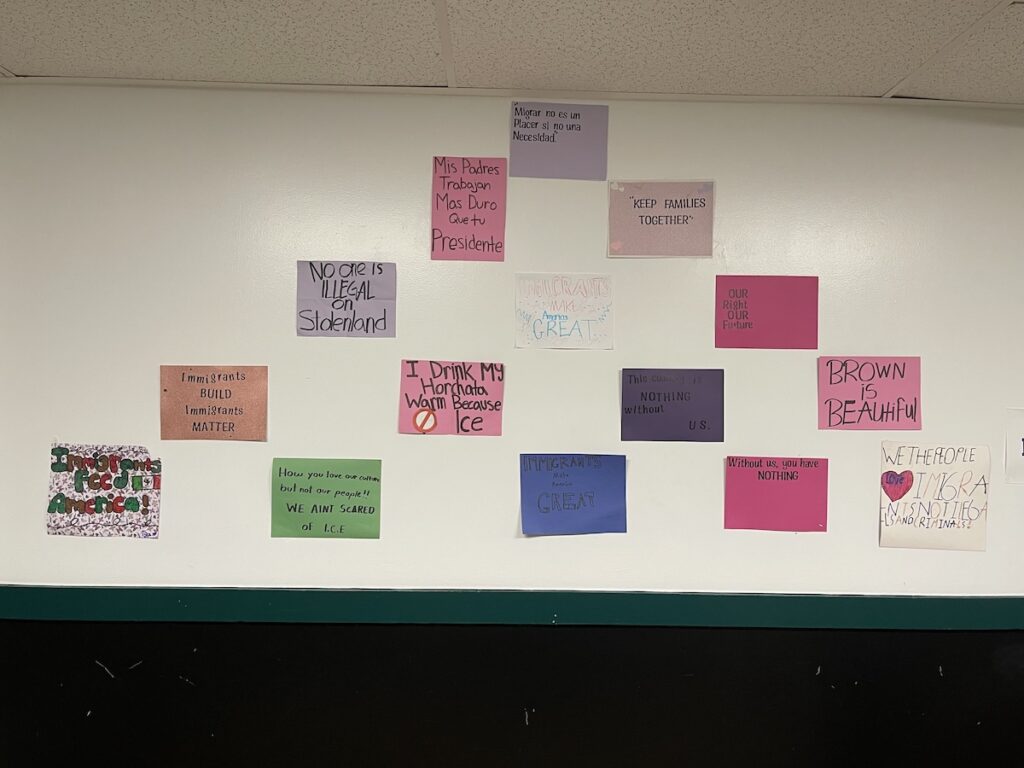

Shortly after, Solis and others created an after-school club with the non-profit CHIRLA, the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights, to help educate his classmates on their rights should they encounter law enforcement. “Being in that club really helped me. I learned from there not to open the door for ICE,” he notes.

That information proved crucial when ICE did come knocking two years later, on February 26, 2019, when Solis’s father was detained. He was ultimately released a month later with the help of lawyers that Solis met through the school club.

Both father and son credit Academia Avance—which offers students immigration-related resources—with helping them get through this uncertain time.

Ricardo Mireles founded Academia Avance in 2004 with the goal of sending more kids from Los Angeles’ Highland Park neighborhood to college. He served as the executive director of Academia Avance until his retirement in October 2024.

“That is what almost any immigrant parent is going to tell you, ‘I came, I sacrificed everything from my country of origin…but I’m doing it for my kids so that they can go forward,’” says Mireles. “And almost always it means so that they can go to university.”

According to Mireles, families trust schools implicitly, leaving their children with teachers and administrators for eight hours a day. So, in times of crisis, he says, schools have to repay that trust.

During Trump’s first term, Academia Avance helped connect parents to organizations with immigration related expertise. Mireles leveraged relationships with immigrants’ rights groups like UNIDOS US, National Day Laborers Organizing Network (NDLON), and CHIRLA. “Those relationships were put to work right away,” he recalls.

Before his father’s detention, Solis worked with Lizbeth Garcia, a high school teacher, on the after-school club. Garcia connected Solis with her sister, Kathia Garcia, a youth programs manager at CHIRLA. Lizbeth Garcia quickly grew to be a trusted source for Solis.

The day Solis’s father was detained, Lizbeth remembers getting a call at 5:30 AM. “I ran across my hallway to my sister’s room, and I said, ‘Hey, it’s happening. We need to make sure that we do something about it.’”

According to Solis, the CHIRLA rapid response network was activated right away. “They got on it and they were trying to work on his case as fast as possible and… it worked out in our favor.”

Solis’ father, Jair Alberto Solis, says he is grateful to the school and to Mireles specifically for helping him after his release. “He always worriesabout the families all around the school. He always asks, ‘What do you need? What’s going on with you? Anytime you need help, come and see me.’”

Mireles even offered up his own car so that Solis could go back to work. The help after release was particularly meaningful, as detention had turned the Solis family’s world upside down. “The worst thing is the effect leaves,” notes the younger Solis. “Now, every knock at the door is trauma for my dad.”

Mireles says while he never doubted the strategy of supporting his students, “There was always doubt this is going to work?”

He remembers one student whose older brother with disabilities was deported to Mexico, even as she juggled multiple responsibilities, as interpreter for the family, concerned sister, student-athlete, and prospective college applicant.

The role of the school is “to support those students in knowing their moment, knowing their story, knowing their challenge and responding to that,” said Mireles. That meant supporting this student taking time off to go to Mexico to check on her brother and offering flexibility with coursework.

In today’s climate, Adriaan is pushing educators to offer even more flexibility. “It is important that we understand that there’s no room for rigidness,” he said, offering as an example how in the past he would collect students’ cell phones to minimize distractions. As immigration enforcement intensifies, “kids need access to check on their parents,” explains Adriaan.

That access can be a double-edged sword, however, notes Lizbeth Garcia, pointing to social media being inundated with reports—accurate or otherwise—of ICE sightings. Students are “constantly being updated on, ‘We saw an ICE agent over here, and we saw a border patrol this.’ They’re constantly being bombarded. It’s this fear that is coming at them.”

She adds, “We cannot operate like this, and our students need to be taught, do not operate under fear.”

Avance is not immune to challenges. In 2017, the school enrolled 397 students. In 2024, enrollment declined by almost 40%. According to the California School Dashboard operated by the California Department of Education, Avance had a 42% chronic absenteeism rate in 2024.

Thomas Dee of Stanford University studies how immigration enforcement affects school enrollment rates. As part of that work, he and his colleagues analyzed counties that made enforcement agreements with ICE from 2000 to 2011.

“We found that the school enrollment of Hispanic students fell by around 10% once these programs came online,” says Dee. His team estimated that almost 300,000 students were displaced by these county level agreements with ICE.

It is unclear where these students went—if they moved to another school district, or self-deported—but Dee says the movement itself can be destabilizing for students. “Dislocation occurring under duress is developmentally harmful to children, particularly when it’s repeated,” he notes.

Dee’s research predates the pandemic, when enrollment dropped even further. “Our schools who are on the front line of trying to address this enrollment crisis, are dealing with a financial crisis, both because of sustained enrollment loss and the expiration of federal pandemic aid that had been available to them,” adds Dee.

Despite these pressures, Avance continues its work. And the impact is undeniable.

According to Solis, if his father had been deported, “I do not know how I would have been able to look out for myself, my little brothers and their future.” Pointing to the neighborhood, he says growing up it was easier to call someone for weed than find someone to help you fill out a college application.

Today, Solis is enrolled at the University of California, Merced, and hopes to attend law school and work as an immigration attorney to help others in his community.