As the Bay Area housing crisis deepens racial and wealth divides, how much is the system working as intended?

With a two century history of race-based discrimination preventing many Bay Area communities of color from finding homes, race-conscious housing plans are needed to mend this disparity, said front-line housing policymakers and advocates at a Monday, January 22 forum held by San Francisco Bay Area Planning and Urban Research Association (SPUR).

The racial history of Bay Area housing

Moderator Geeta Rao said these racialized housing policies began before the 18th century with the divestment of land from indigenous Americans, and continued well through the 20th with exclusionary zoning and redlined maps; racialized public housing; covenants prohibiting property sales to minorities; and blockbusting, in which developers convince residents to sell below market due to an alleged influx of minorities.

Decades after California Fair Housing Act of 1959 and the federal Fair Housing Act (FHA) of 1968 outlawing racial discrimination in housing sales, renting and financing, the legacy of this discrimination remains, added Rao, senior director of Enterprise Community Partners.

In the U.S., Black family incomes are about 60% of white incomes, yet the housing wealth of black families comprises 5% of white ones.

In the Bay, the Black population comprises 30% of the region’s homeless population — five times higher than its 6% share of the general population.

“When the U.S. first cut its teeth on mortgaging, they weren’t mortgaging property but people,” said Wilhelmenia Wilson, executive director of Healthy Black Families. “My father sold our house in north Berkeley in the 1950s; as a state attorney, he got the memo about the incoming BART train station. Now, I work there in a landscape made ripe for mass displacements of African Americans who never got that memo.”

This displacement of housing for communities of color is historically allied with exclusionary single family zoning where there is new development — “particularly in the South Bay,” said Mathew Reed, policy director at SV@Home.

“Many regions, like San Jose, essentially didn’t exist before World War II as we know them now,” he added. “They grew under public investments like the GI Bill, which subsidized overwhelmingly white Americans into the homeowning middle class.”

Bay Area cities with at least 85% of residential land zoned for single families have home values over $100,000 higher, with households nearly 20% whiter, than elsewhere in the Bay.

Even though the FHA outlawed discriminatory housing policies, Congress debates around the bill racialized the distribution of resources by turning control of home financing over to local realtors.

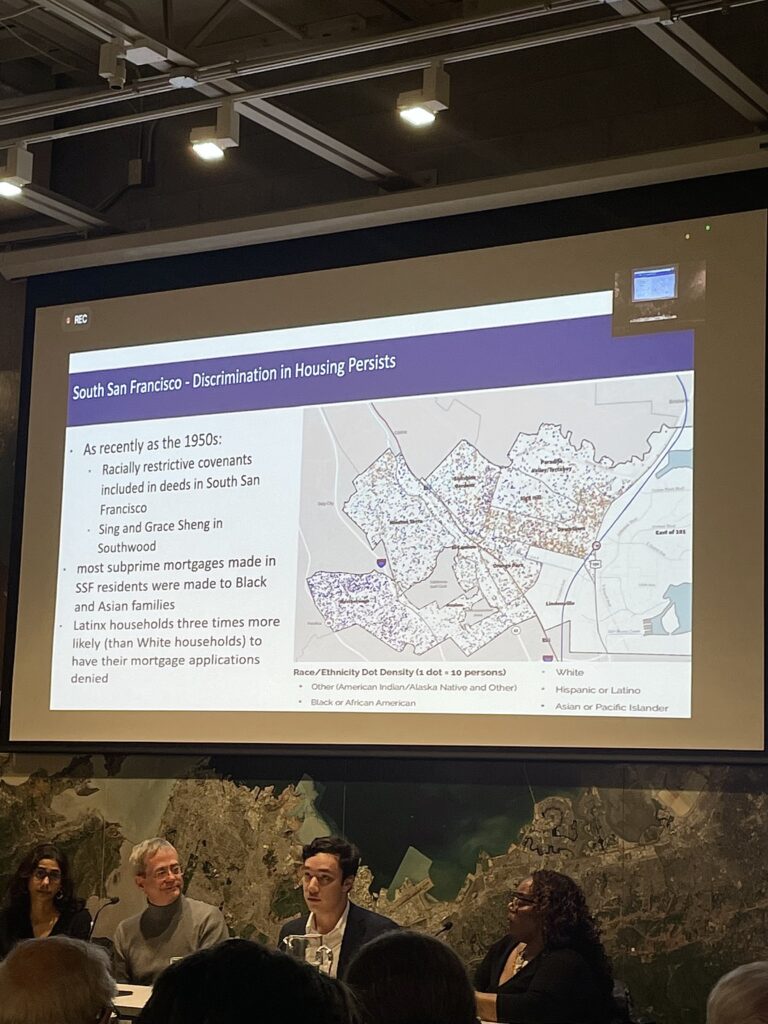

Even 15 years ago, “predatory lending of subprime mortgages was central to the Great Recession” and disproportionate foreclosures among Black and Latino homeowners, Reed said.

A SPUR report released on January 23 found that even for such a high-cost region, the Bay produced by far the least per-capita and per-job housing from 2010 to 2020 among 25 comparable U.S. cities who shared a population greater than 1 million; a population density greater than 100 people per square mile; an average commute less than 40 minutes; an annual job growth rate over 1% per year; and residents who largely voted for Joe Biden.

As one of the youngest U.S. elected officials, South San Francisco Mayor James Coleman — having entered office at age 21 — said this experience of precarious, expensive housing was a mainstay for his upbringing in the Bay: “People I graduated high school with still DM me on Instagram and say: ‘When are you going to build affordable housing?’ Because they grew up here and would love to afford returning, but the landscape is so unequal.”

Because 74% of single-family homes in South SF were built before the 1968 FHA, generational property wealth is still segregated staunchly along racial lines citywide.

In the southwest neighborhood of Westborough, for example, 72% of families are Asian, whereas 20 to 30% are elsewhere. Residents downtown, which houses under a fifth of the city, are similarly far more likely to identify as Latino compared to citywide averages.

What’s working?

Such segregation is best broken at the ground level, Coleman continued.

“In 2021, particularly for our Spanish-speaking community, our city created a program where we hired two to three people whose job was to literally knock on doors and ask residents what they struggled with most … We found it was rising rents.”

Even with aid like state and federal COVID rent and mortgage relief programs, language barriers unaddressed by local governments prevent those who most need the assistance from accessing it, he noted.

Additionally, Coleman added, South San Francisco passed a 20%-margin majority measure in 2022 superseding Article 34 — a segregationist state measure passed in 1950 giving wealthy neighborhoods veto power over affordable housing.

“Because the history of housing here is the history of racialized displacement, encouraging affordable housing is a race-conscious policy in of itself,” noted Reed. As the state invests in housing, it focuses development in “resource-rich communities” — i.e. areas with high income, educational outcomes and public infrastructure.

However, oftentimes the outcome of this is that low-income residents are displaced from neighborhoods they’ve lived in all their lives, he continued. “The expansion of opportunity is well-meant, but we’re pushing back on the narrative that lower-income communities aren’t worthy of investment too,” by supporting returning-tenant preference programs.

Affording affordable housing

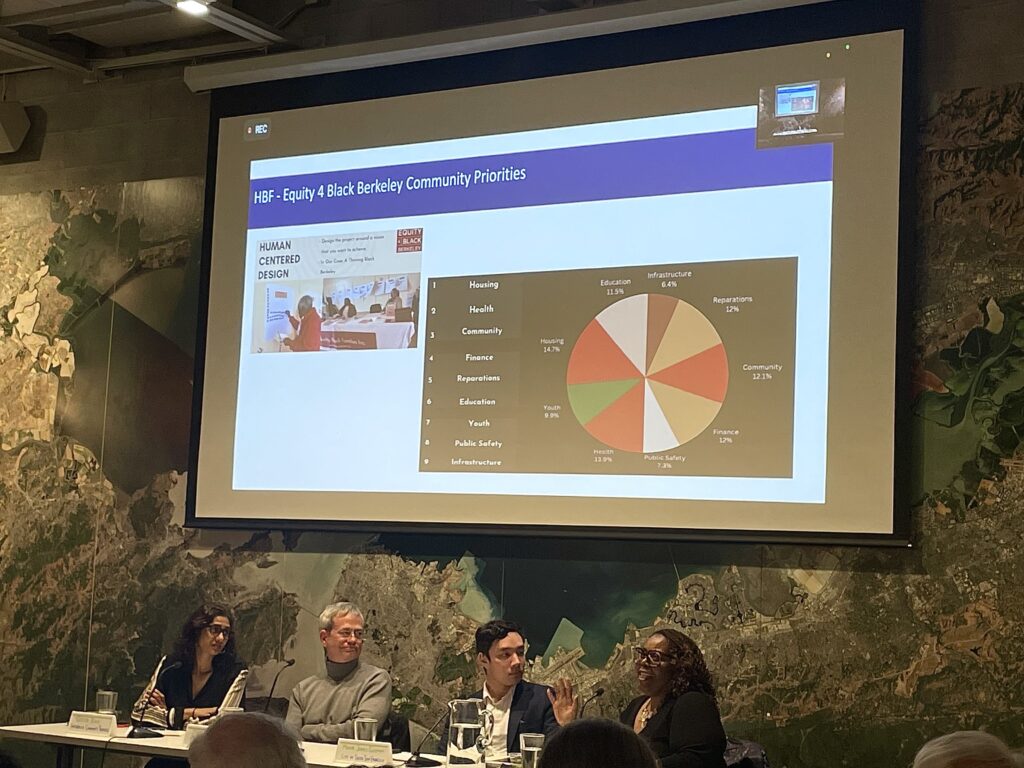

With Healthy Black Families, the city of Berkeley has been ground zero for one such program. Building on a prior “right to return” survey the city released last year, the nonprofit asked Berkeley residents in-person and online — especially those near the North Berkeley and southern Ashby BART stations, where future affordable housing units will be built — “What do we need to create a thriving black Berkeley?”

“Across four months, through our initiative Equity 4 Black Berkeley, we compressed 1,600 inputs into nine categories,” she continued. ‘Housing’ was the foremost response, just above ‘Health’ and ‘Community.’

This feedback informed an Affordable Housing Preference Policy for displaced residents which the City Council passed unanimously last July, effective this year.

“Engaging your community to find out what they need isn’t a checkbox, it’s a cycle — and so is the history of black progress and majority retaliation,” Wilson said. “I find that when you walk into communities that have been devalued, even the capacity to dream takes building the capacity to trust, the will to share.”

Black respondents’ priorities generally differed from non-Black allies in a greater emphasis on community and finance, she remarked. These were interdependent for many Black residents “because creating affordable housing without also creating opportunities to afford housing” — like limited-equity co-ops that give people a stake in their community — “is just a welfare state.”

“My father used to say ‘You can’t legislate relationships, you have to build them,” Wilson continued. “Even the city told us early on — ‘If the community doesn’t show up, it’s a wrap.'”

On the way here, I dropped by our office and a woman was standing outside asking how moving back to Berkeley worked under the affordable housing policy,” she added. “To want to show up for their community, people need to see the outcomes of community.”