HOUSTON, Texas—Erlinda Walker has lived in Houston since the early 1980s. During that time, she recalled, Asian American and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) were hardly seen in the metropolitan area, where she and her first husband settled.

“Other than myself and a close Vietnamese friend, whose husband was stationed at Fort Sam Houston military base, sometimes I would not even see any Asian person for weeks,” said Walker, who is originally from the Philippines.

Because the AAPI population was “practically invisible” until the 1990s, she knew it would have been nearly impossible for an electoral candidate of Asian descent in Harris County, where Houston is located, to win a congressional seat.

Today–some 40 years later–the AAPI population in Harris County and neighboring areas has quadrupled. Nearly every block for a long stretch of Bellaire Boulevard—the heart of the Chinatown district in southwest Houston—is filled with Asian restaurants, shopping malls, warehouse-sized supermarkets and retail services.

While those numbers have given hope to Asian American voters, like Walker, that someone who looks like them will be elected, the odds in fact may have grown even slimmer. The culprit: Texas lawmakers have drawn new redistricting lines that cut through heavily Asian neighborhoods.

Since new political maps for the state’s congressional, legislative and State Board of Education districts have been approved, there has been a public outcry from Asian American communities and advocates, pointing out that they were drawn to diminish the power of AAPI voters and other voters of color to keep Texas Republicans in power for the next decade.

Texas Gov. Gregg Abbott, who is a Republican, approved the new redistricting maps in October 2021. The new districts, based on the redrawn lines, will be used for the first time in this year’s primary and general elections, preventing any court interventions.

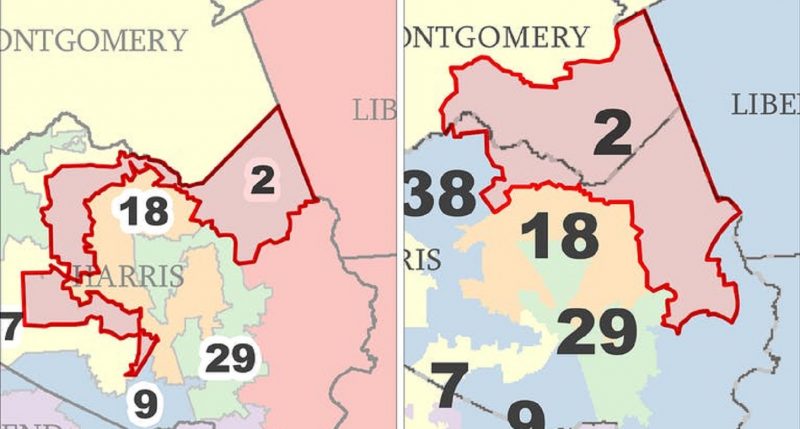

“Our state and congress have failed Asian Americans,” Ben Chou, an elections attorney and former senior advisor for the Harris County Elections Office, said at a recent press briefing with ethnic media, hosted by Ethnic Media Services. “The new map has intentionally diluted our community, breaking and slicing Asian American communities into three.”

Since 2010, according to the 2020 U.S. Census, nearly 1 in 5 new Texans are Asian American. The AAPI population increased from about 950,000 in 2010 to nearly 1.6 million in 2020.

Fort Bend County—the wealthiest county in Texas, located about 30 miles west of downtown Houston—has the highest proportion of Asian residents in the state. The population of its residents who identify as Asian increased by almost 84 percent in the past decade, the census said, making up 22.2 percent of 2020 residents.

But with the latest gerrymandering efforts, AAPI populations in Fort Bend County have been spread across three congressional districts by new lines drawn straight through the Asian neighborhoods. Some of these heavily Asian neighborhoods are now part of a white-majority rural district, decreasing the percentage of the Asian population by more than 15 percent.

Previously, more than 11 percent of the eligible voter populations in some parts of Harris County were Asian American. Under the new approved redistricting lines, however, the percentage of AAPI population in those areas will decrease to around 9 percent, weakening its voting power as a community.

Chou, who is of Chinese descent and currently running for Harris County commissioner, joined fellow Asian American advocates who believe that AAPI political power has been weakened under new congressional maps.

“I have been doing the work in and around the census and redistricting for over three decades now,” said Debbie Chen, executive vice president for OCA-Asian Pacific American Advocates. “In some ways, it’s disheartening that every 10 years we still are having the same conversation.”

What has been different in the last decade is the surge in the AAPI population in the Houston metropolitan area, according to Chen, which could have been a ripe “opportunity” to elect an Asian American candidate in congress—if the new maps had not been drawn.

Presently, the Justice Department and various community groups representing Latino, Asian and Black voters have filed lawsuits, challenging the new political maps and saying that lawmakers have intentionally violated the federal Voting Rights Act.

While these lawsuits have been shuffling through state and federal courts in Texas, because the AAPI population is still a relatively small fraction of the state population as a whole, political experts say redistricting lines that specifically target Asian American communities may not have violated the law.

Still, Walker–who volunteered in get-out-the-vote initiatives in the last elections–is optimistic that the AAPI community can still elect an Asian American candidate.

“It’s time for Houston or around Texas to elect an Asian American,” said Walker. “We’re the fastest growing population in the state, and we definitely have a powerful voting bloc.”

The hope for the AAPI community to have equal representation in the next decade may be an elected position in the state.

Lydia Ozuna, president of Texans Against Gerrymandering, stressed that by going to the polls and casting ballots would be an effective strategy for Asians, along with Blacks, Latinos, Native Americans and other underserved communities.

“People who understand how voting is important, how voting affects their lives, are the ones who most likely participate in the elections,” she said.

In the last presidential election, according to Edison Research for the National Election Pool, about 3 percent of voters in Texas identified as Asian American.

“We can’t be gerrymandered outside the state. No matter how they redraw the lines, we will always be a part of Texas,” said Niloufar Hafizi, outreach director for Houston-based Emgage USA. “If the majority of Asian voters come out and vote, we can still be the decision-makers of who we want to elect.”