Above: Surviving Hmong veterans of America’s Secret War in Laos, which claimed between 35,000-40,000 lives, gathered for the May 18 event in Marysville, California commemorating Hmong-Lao Veterans Day. (Credit: Peter Schurmann)

MARYSVILLE, Calif. – An event honoring Hmong veterans of the American Secret War in Laos was held Saturday in Marysville, about 40 miles north of Sacramento. Dozens of surviving veterans, alongside community activists and local dignitaries were on hand.

The event is part of a decades-long effort to gain recognition for the Hmong community’s sacrifice and their place in this little-known piece of American history.

“Thousands died fleeing Laos on May 14,” noted longtime community advocate Steve Ly. “May 15 was the day they became new Americans,” he continued.

Ly served as mayor of Elk Grove, south of Sacramento, between 2016-2020 and was the country’s first ethnic Hmong to serve in that position.

Between 35,000-40,000 Hmong were killed in a covert CIA operation intended to thwart communist forces during the height of fighting in Vietnam. The operation ran through both the Johnson and Nixon administrations and resulted in almost 2 million tons of ordinance dropped on both sides of the Vietnam-Laos border, despite the latter being a neutral country. Congress was never informed.

A ceasefire agreement was reached in 1973 and two years later the communist Pathet Lao took control of Laos. Thousands fled the country in the ensuing years, many arriving in America as refugees.

Yet their contributions to the American war effort continue to go largely unrecognized. Hmong veterans, including those in attendance Saturday, are still not acknowledged by the federal government and do not receive VA benefits.

“Every Hmong soldier that fought and died and was wounded represents an American soldier that didn’t have to go through that injury or death,” said Yuba County Supervisor Seth Fuhrer, who delivered a proclamation on behalf of the county recognizing May 15 as Hmong-Lao Veterans Day.

California is home to the US’s largest Hmong population, at roughly 95,000, with communities concentrated up and down the Central and San Joaquin valleys. Wisconsin, Minnesota and more recently Alaska and some southern states are also home to large Hmong populations.

Saturday’s event, Honoring the Forgotten Heroes, was held at Veterans Park in Marysville, which welcomed one of the earliest waves of Hmong arrivals to the US in the late 1970s and early 80s. A large portrait of the late Gen. Vang Pao, who was instrumental in helping the CIA recruit Hmong fighters, adorns the stage behind the lectern.

The event was organized by the non-profit Sacramento Hmong American Resources and Education (SHARE) and the Yuba-Sutter Hmong American Association.

“Many people we talk to still don’t know who the Hmong are,” said SHARE President Marie Vue. “They still don’t know why we’re here. They think we’re here as immigrants. We’re actually refugees. And they don’t understand the difference.”

Vue continued, “That’s what we’re trying to get out there. This is who we are.”

Part of that effort involves incorporation of the Hmong experience into the public-school curricula for California high schools, an effort that got underway more than 20 years ago after the CIA declassified documents pertaining to the war.

In 2003 state lawmakers approved AB 78 recommending inclusion of the Secret War in social studies textbooks. It took until 2018 for the recommendations to be added to the state’s education codes. Yet today there is scant mention of this history in most classrooms.

“We don’t need a whole chapter,” stressed Kevin Xiong, president of the Hmong American Association and a leader in the effort pushing for Hmong inclusion in California classrooms. “We need a small lesson on who these people are. Why are they here.”

He added, “We were part of the war. We made sacrifices. We are part of you. Just recognize us,” he said.

Rob Gregor is the Yuba County Superintendent of Schools and has worked in education for more than three decades, during which time he hired the county’s first Hmong administrator who would go on to become Yuba County’s first Hmong principal.

“Some things go quickly, and some things go slowly,” he remarked as to why Hmong history is still not being taught, noting the process often depends on “how loud” the voices are. “And this one has not taken off as quickly as we would like to see.” Still, he noted, “I believe we will see momentum, especially in places like Fresno, Merced, Modesto,” cities with sizable Hmong communities.

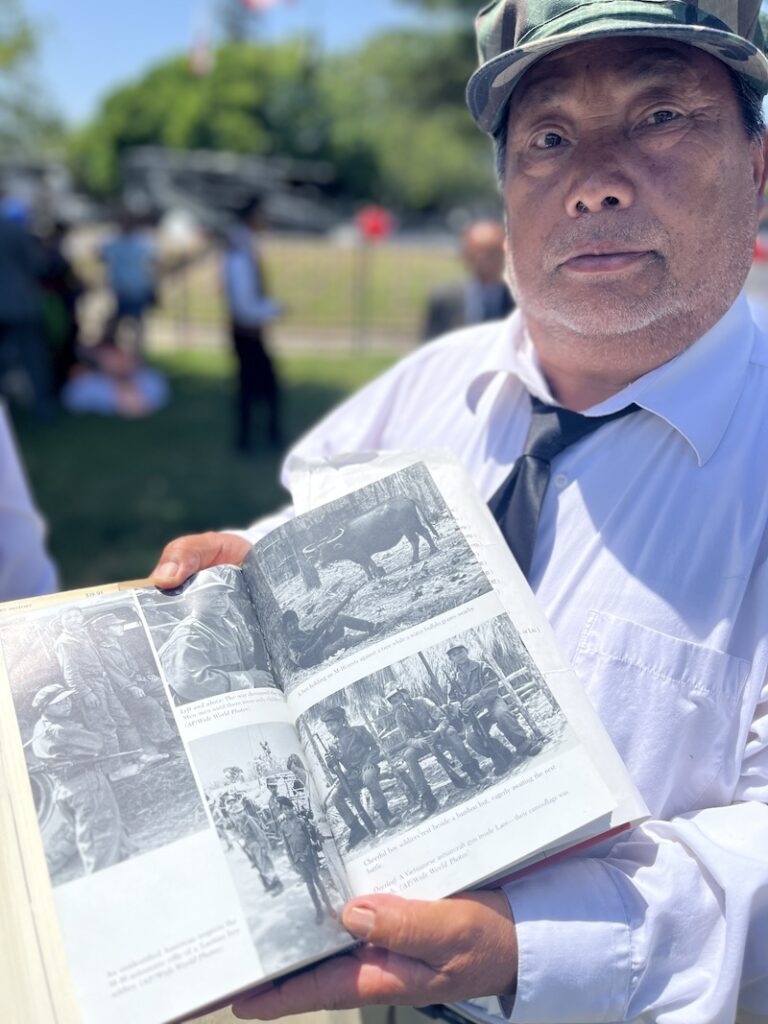

That’s welcome news for Chai Vang. Now in his 70s, Vang was a 13-year-old village boy when he was recruited by Gen. Pao to fight against communist forces for the CIA. He lifts up a book, Ravens, about the Hmong air reconnaissance pilots trained to fly spotting missions identifying North Vietnamese redoubts, and points to a photo of a young boy in fatigues.

“That’s me,” he said, adding, “It’s an honor to be here. It’s an honor to be recognized. And to be known as someone who actually served the US military, especially considering all the friends and peers who have passed.”

One of those deceased is Ly’s own father.

“Part of the frustration with the Hmong community, and my personal story is the same, is my father used to tell me these cloak and dagger stories, and I thought he was nuts,” he said. “It didn’t occur to me that there was truth to this until a lot of the information was declassified.”

Ly points to the miniature American flags lining the walkways, explaining how each represents a fallen Hmong soldier.

“There is a tendency on the part of the general public to just lump everyone together,” he remarked. “I am a firm believer that everyone has a story… one that, if you take the time to learn it, you begin to value the reasons why people are here.”

This resource is supported in whole or in part by funding provided by the State of California, administered by the California State Library in partnership with the California Department of Social Services and the California Commission on Asian and Pacific Islander American Affairs as part of the Stop the Hate program. To report a hate incident or hate crime and get support, go to CA vs Hate.