A grassroots organizer in Stockton, California says funding strategies during the pandemic left community based organizations like his scrambling.

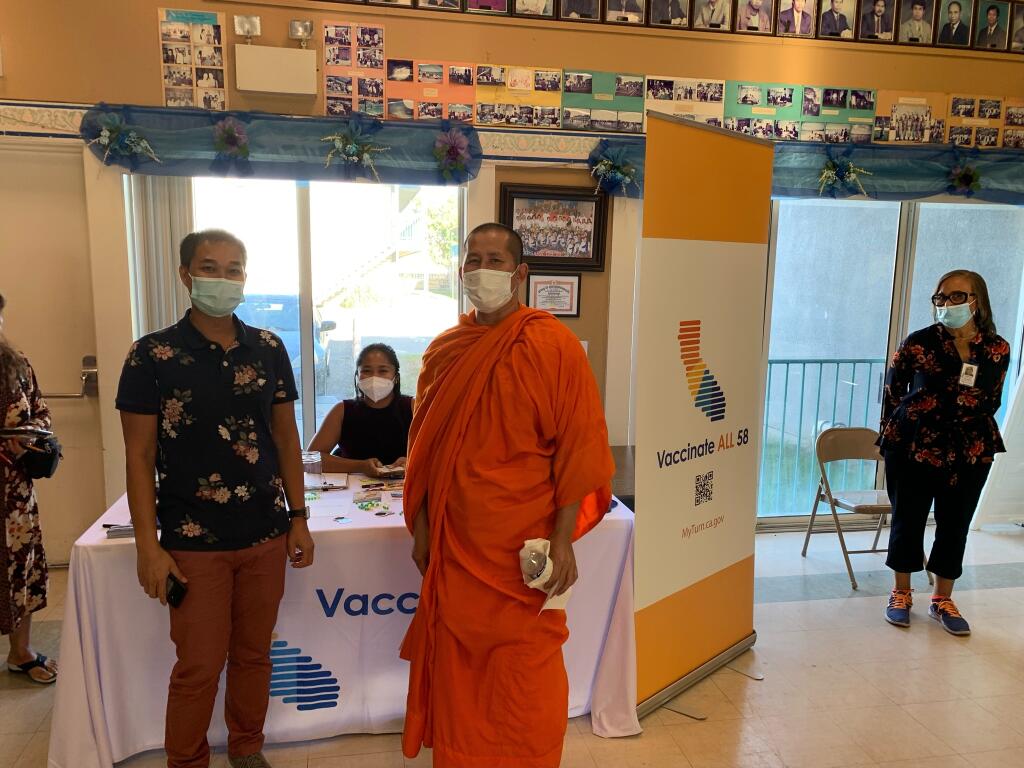

Editor’s Note: This is the first in a series of conversations with leaders of community-based organizations (CBOs) across California that EMS will be publishing about their experiences on the frontlines of fighting the COVID 19 pandemic. The series will look at how grassroots organizations responded to the public health emergency, and what impact that effort had in helping narrow the gap in healthcare access for vulnerable populations. (Above: Vaccine clinics like this one, organized by the CBO APSARA, provided critical access for Stockton’s large Cambodian community.)

STOCKTON, CA. — Sothea Ung directs programs for a 33-year-old nonprofit organization in Stockton, a suburban enclave 90 miles east of San Francisco, which proved indispensable in getting COVID 19 vaccines to that city’s sizable Cambodian refugee community.

What keeps Ung up at night, he says, is that his agency, APSARA, was excluded when local civic leaders met to plan an emergency vaccine rollout campaign to reach Stockton’s increasingly diverse and underserved populations.

“We’re a small agency that wasn’t invited to the strategic planning sessions at the start,” Ung recalled. The result was a top-down campaign where funds were disbursed to the largest nonprofit agencies and only slowly trickled down to grassroots groups that often have the most direct ties to the communities that need to be reached.

“The voices of the small CBO’s need to be heard. We need to build prevention paths that will ease the burden on the health care system over the long term,” Ung stressed.

He added there needs to be more transparency in how federal funds get allocated. The funding for COVID 19 was short term and not an investment in long-term infrastructure, leaving structural disparities in health care access unaddressed.

Although Stockton was eventually successful in raising the county’s vaccination rates and bringing down infection rates—from among the state’s highest to among its lowest—Ung warns that without a shift in strategy, the county will have to repeat the cycle all over again when another pandemic hits.

How APSARA helped Cambodians navigate through the pandemic offers a case study in how hundreds of CBO’s across the state—fragmented and under-resourced—nevertheless provided the backbone for reaching the state’s most underserved populations.

The lesson looking forward according to Ung: “We need to reshape the funding pyramid from the bottom up.”

APSARA was founded in 1989, when a group of 35 residents of the Park Village housing complex decided to do something about its rapidly deteriorating unsafe conditions.

Four years later they purchased the Apsara Park Village complex from the federal Housing and Urban Development agency for $1 and transformed it into a verdant oasis of buildings rimmed with small garden plots of Asian vegetables, fruit, flowers and palms.

“Our main purpose was to help immigrants overcome poverty and live safely,” said Ung, who joined APSARA in 2012 after immigrating with his family from Cambodia where he had worked as a community organizer.

When the COVID pandemic hit in March of 2020, APSARA became a lifeline for its more than 2,500 clients, most of whom arrived as refugees fleeing a mass genocide, the Killing Fields and are now in their late 60s and 70s. Most do not speak English and lack access and the knowhow to navigate the internet.

“There was a huge communications barrier, as people navigated through the complex systems of support services,” said Ung.

The mandated social distancing protocols meant that many families were separated from loved ones who might have been able to help. As the virus spread, many people in the community lost their jobs, largely in the agricultural sector or warehouses. Some were left homeless.

“The pandemic changed everything,” Ung explained. “The community lost its balance. There was no peace anymore—people were reluctant to walk anywhere after dark.

“APSARA used our existing programs to bring knowledge to people to help them access the services they needed,” Ung said.

The organization launched a phone line with volunteers who spoke Khmer, Thai, French and Spanish. It also offered interpreter services for patients who needed to speak to their physicians. “We wanted to make sure that people were getting the answers they needed.”

As early as March of 2021, Ung began organizing vaccine clinics at the Apsara Park Village apartment complex, successfully vaccinating a large percentage of residents. Buoyed by its success, it began putting out the word on social media about its second COVID vaccine clinic in May. The team told people at public parks during weekend picnics and did outreach via cell phone and blog posts. Friends told friends.

The grassroots strategy worked: at the second clinic, entire families as well as dozens of elderly refugees came from as far as Lodi, more than 16 miles away, Modesto, French Camp and even Merced.

“They came to our clinic because we were the only place with a Khmer translator and where they felt comfortable,” Ung said. “People could ask questions about the vaccine, and our staff could translate them for the medical personnel. We didn’t want to persuade them—we wanted them to get vaccinated based on their own knowledge, and to help other families make that decision for themselves.”

Throughout 2021 and 2022, APSARA organized vaccine clinics every other month which to date have collectively vaccinated more than 2,100 people.

“We would see 100-120 people at every clinic,” said Ung, including many from outside Stockton drawn by the in-language services. The organization teamed up with larger regional organizations like El Concilio and Catholic Charities to get the necessary vaccines.

Ung says rescue funds only became available towards the end of 2021, and even then, it was the bigger organizations that received the lion’s share. APSARA and other grassroots groups had to rely on trickle down funds. Grants that they were able to raise came with three- or six-month timelines, which made it difficult to hire staff and sustain initiatives.

Despite that, APSARA continued its COVID 19 vaccine clinics which today focus on updated boosters. But interest in the boosters has been low, Ung says. People hesitate, wondering why they should get the vaccines if they might still get COVID.

What worries Ung most is a shadow pandemic in the Cambodian refugee community that COVID 19 exposed and exacerbated. Many of those who escaped the Killing Fields suffer from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and other mental health issues.

“Our mental health needs are enormous,” said Ung, who hopes to get his voice heard about the need for mental health services for his community.

“People have to understand the system, but the system is not easy to understand,” Ung concluded. “I’m not scared of COVID. I’m scared the system is not prepared.”

EMS Executive Director Sandy Close contributed reporting for this story.