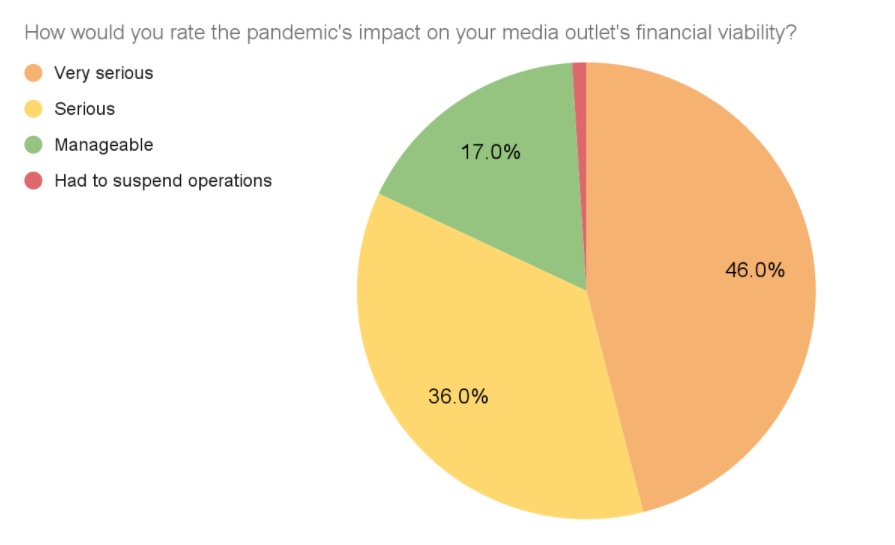

Two years into the COVID-19 pandemic, the vast majority of California’s ethnic news media are still in operation despite 82% of outlets having experienced “serious” or “very serious” financial losses, according to an online survey conducted by EMS. Some 58% reported that their revenue had increased slightly in 2021 over 2020, and 6% reported substantial gains.

The survey engaged a cross section of print, online and broadcast media – 83 respondents in all – serving 18+ distinct language groups targeting major ethnic and racial audiences including Black, Latino, Chinese, Korean, Filipino, Vietnamese as well as Tongan, Burmese, Native American and Indigenous.

“Ethnic media have proven to be remarkably resourceful in the face of enormous odds,” said Sandy Close, EMS director, summarizing one key takeaway from the survey. But the costs have been high in terms of reduced news content, some loss of audience reach, and a consequent limit on the sector’s capacity to challenge the spread of disinformation among their audiences.

Respondents credit their survival to a variety of strategies including volunteer labor – cutting their own pay to sustain their businesses.

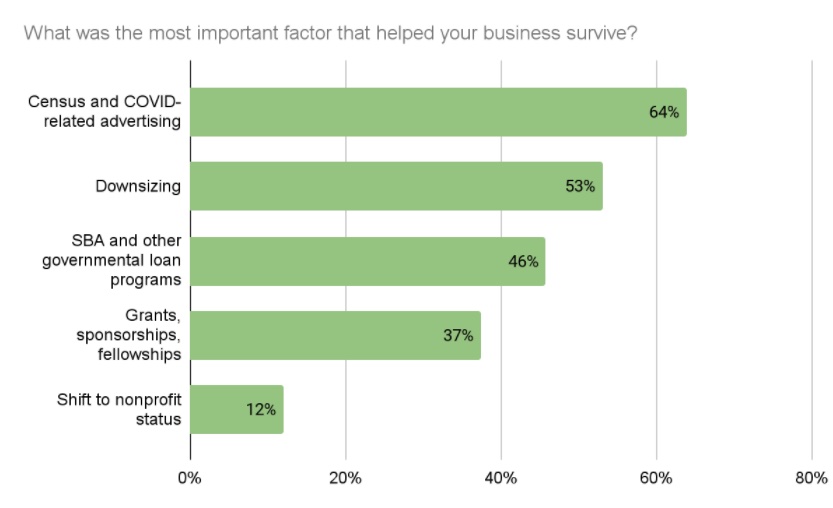

A large majority – 63% – say advertising related to promoting the 2020 Census and COVID-19 and vaccine campaigns helped most to offset steep revenue losses. Downsizing was the sector’s second most important survival strategy, followed by the SBA loan program.

Across print, digital and broadcast outlets, the largest areas for cost cutting were newsrooms and administration, followed by equipment and studio costs. Some 15% of print outlets either suspended printing and pivoted online during the pandemic, or greatly reduced the number of print copies.

Cutbacks in reporting staff forced over half of media respondents (53%) to reduce their news content especially in culture, sports and entertainment, and public affairs. Most outlets said they prioritized hard news, community advocacy, home country news and economic coverage, as well as news about the pandemic.

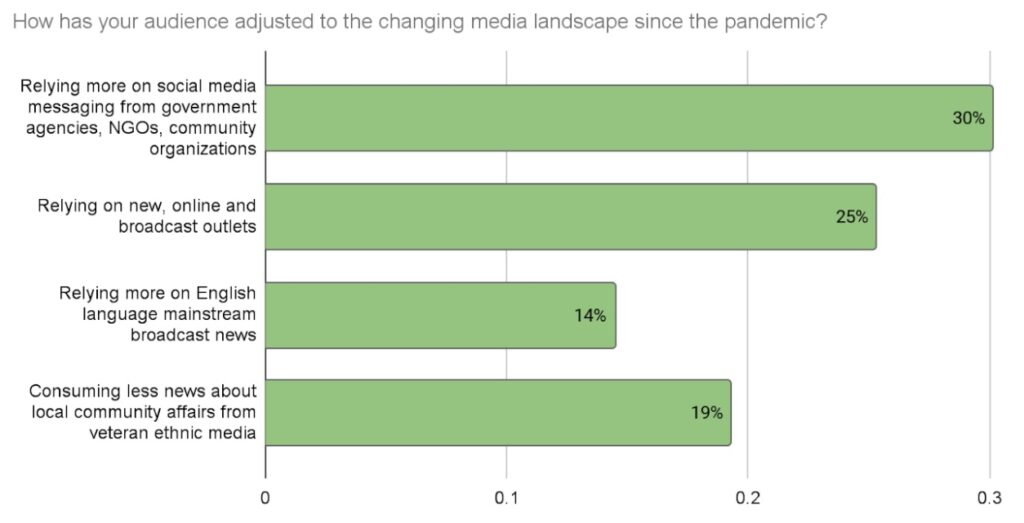

Asked how their audiences adjusted to the changing media landscape since the pandemic, 30% of respondents say people now pay more attention to social media messaging from government and nonprofits and 25% to new online information platforms to get the information they need. Twenty percent of respondents speculate that their audiences are relying less on ethnic media.

“This is one reason why disinformation is spreading so fast in some immigrant communities,” says Jongwon Lee, a Korean media specialist and lawyer. “New online platforms draw audiences away from traditional print and broadcast ethnic news outlets because they are filled with sensationalist news. It’s tough for print journalists to compete head-to-head with the online platforms.”

Veteran Chinese newspaper reporter Rong Xiaoqing sees the same thing happening in the Chinese media as online platforms proliferate to target recently settled Chinese immigrants and cannibalize Chinese print media for their news content.

Yurina Melara, a veteran reporter for Spanish language media who now works on communications for the California Department of Public Health’s Vaccinate All 58 campaign, says Latino media had to let go of their newsbeat reporters. “It used to be that Spanish language broadcast could draw on Spanish language print for in-depth reporting on topics like politics, health care, immigration. Now everyone works on general assignment.”

To secure their future, 78% of respondents say their top priority is finding predictable ad revenue, followed by expanding digital content to sustain and expand audience reach. The obstacle here is that there’s little revenue to be gained from digital advertising, which is just a fraction of what ethnic media earn from print and broadcast ads.

“With Facebook and Google earning the lion’s share of ad revenues, ethnic media lack the financial incentive to invest in digital capacity, but they also know it’s essential to staying relevant to their audience. This is the same bind they faced before the pandemic, only now they have even fewer resources,” says Close.

Respondents ranked rebuilding their newsrooms as their next highest priority. In fact, for most ethnic media leaders, it’s been newsroom cutbacks that have hurt the most.

Vandana Kumar who, with her husband Vijay, publishes India Currents in Silicon Valley, pivoted just before the pandemic to an all-digital format and then applied for nonprofit status. “We have chronicled the lives of South Asians in Silicon Valley for over 40 years—we couldn’t let the pandemic stop us, even if it meant working pro bono so we could pay our writers.”

“We got into the field because we wanted to tell the stories and do the reporting that matters most to our communities,” said Malcolm Marshall, publisher of the Richmond Pulse who trains young people to be the eyes and ears of Richmond’s neighborhoods. “Without our own reporters, we lose the reason why we exist.”

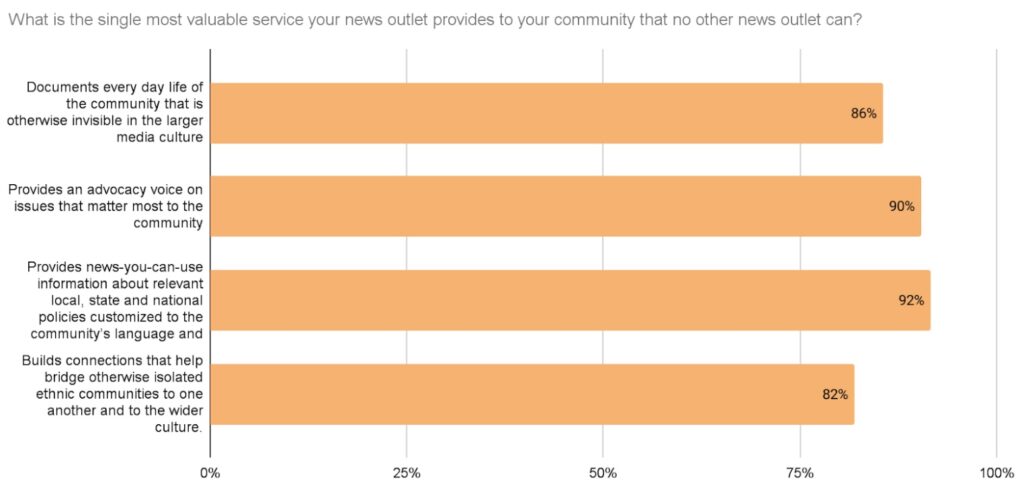

Asked what their unique role is in the media landscape, 60% of survey respondents said documenting the lives of their communities, 67% said providing critical and useful news, and 67% said amplifying community concerns.

“Years ago, then-publisher of La Opinion Monica Lozano said what made ethnic media unique was their commitment to community even when that meant ignoring red lines in their accounting books,” Close recalled. “Ultimately these are mission-driven media. The good news in the survey is that they do whatever it takes to serve that mission.”

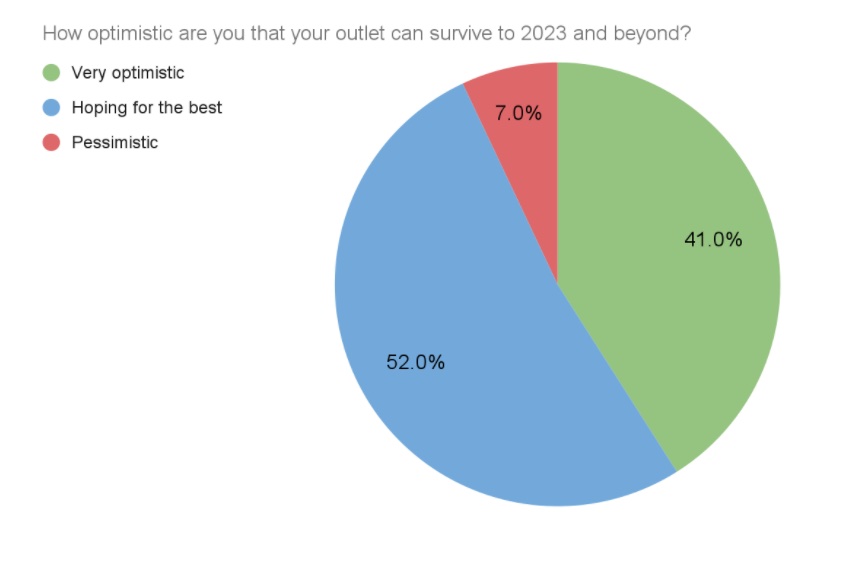

Asked about the future, over 41% described themselves as very optimistic; 52% said they were “hoping for the best.” Only 7% said they were pessimistic.