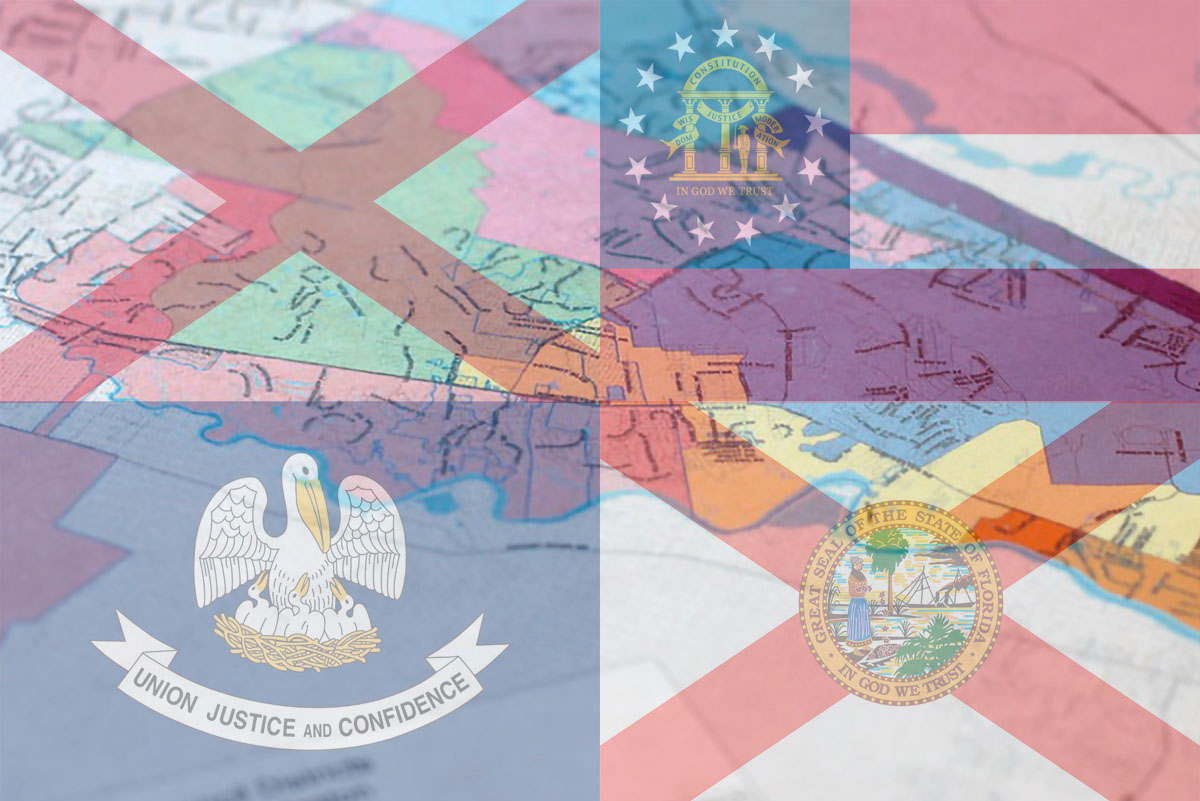

At a webinar in late October, community activists working in Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, and Alabama discussed the challenges and importance of the redistricting process that will affect people’s voting power and rights of self-determination for the next 10 years.

Although redistricting may at first seem removed from the day-to-day concerns of the public, in fact, it’s fundamental to how the U.S. government functions.

“The way our local districts are drawn today is crucial for our communities’ future,” moderator Jennifer Farmer said in introducing the panelists. “It determines our say in who represents us and what resources we get, including funding for schools, parks, libraries, hospitals and social services.”

Furthermore, she added, district maps enacted this year will not only come into play in next year’s election, they’ll remain in place until after the next national census, in 2030, provides an update on data about who lives where, and thus what regions warrant more – or less – political clout.

Based on U.S. constitutional promises of equal representation, redistricting and its implications are one of the arguments activists made in urging people to be counted in the 2020 Census – that new population data gathered in the decennial census drives crucial decision-making for the next decade.

“We are picking right up from our census work, and moving right into redistricting,” said panelist Ashley Shelton, executive director of Louisiana’s Power Coalition for Equity and Justice.

“We’ve got just one shot at trying to increase voice in a state that has the second-largest black population and more than 40% communities of color,” she said.

Redistricting is intended to ensure equal representation and to counter the so-called “gerrymandering” process by which incumbent politicians choose who they’ll represent, rather than the voters choosing who will represent them.

Historically, incumbents of all parties have “packed” or “cracked” communities to limit their power, either by concentrating communities into a single district even though their numbers are strong enough to sway elections in multiple districts, or by splitting those communities among several districts to the point that the community can’t sway any.

Maps drawn with such intent that survived the legislative process have, in some instances, been struck down by courts.

But this year is the first time since the 1965 Voting Rights Act became law that the U.S. Justice Department will not be reviewing changes in election processes in historically discriminatory states to make sure they’re being fairly applied.

This is because since the last round of redistricting, following the 2010 Census, the U.S. Supreme Court, in its 2013 Shelby County (AL) vs. Holder decision, ruled the landmark 1965 Voting Rights Act’s Section 5 that mandated “preclearance” by the Justice Department of significant proposed changes was no longer necessary.

As a result, said Evan Milligan, executive director of Alabama Forward, “We don’t have the mechanisms that we once did to hold our governments to account, at least in terms of the Department of Justice. So that leaves us in a more vulnerable position than we’ve been in previously.”

Alabama

Among its efforts, Milligan said, Alabama Forward has been offering trainings on maptitude and other tools “that most of our legislatures are using” on how to place data into visual maps to propose fair districts.

In all four of the states under discussion at the Oct. 26 event, the redistricting process is done by the state legislature, with the governor having the power to veto maps the legislature approves.

Florida, Georgia, and Alabama, however, are so-called “trifecta” states in which one political party – the Republican Party, in these cases — holds both the governor’s office and majority control of the state legislature.

Louisiana

In Louisiana, where state government is divided between the major parties, it’s possible that the GOP advantage in the state legislature is enough that it could override Democrat Gov. John Bel Edwards if he were to veto their new map proposals.

Florida

Florida’s population has grown to the extent that it gained a new seat in Congress. State law does not require public input in the redistricting process, and in the past, courts have had to intervene when the proposed maps seemed unfair.

Florida Rising and its partners have been demanding transparency in the redistricting process, and launched a website for Florida-specific comment that also offers a mapping program to solicit community map proposals. It provides outreach materials in Spanish, Haitian-Creole and English, the organization’s Mone Holder said.

Jamara Wilson, of Equal Ground out of Orlando, FL, also cited using multilingual approaches to communicating, educating and including more people in the redistricting process.

“Folks really don’t know what their role is in the redistricting process, or how they can contribute to the process or how they are impacted,” she said.

Georgia

Karuna Ramachandran’s Georgia Redistricting Alliance is another veteran of the 2020 Census complete count campaign, which documented how most population growth in the United States over the past decade has been among communities of color, who are now the majority in Georgia.

She spoke of how even in our pandemic-challenged era, public involvement and engagement in the public hearings on redistricting has been strong, perhaps exceeding some expectations.

But it remains to be seen, she said, if the legislature’s maps will reflect that community input. In the past, Georgia’s proposed new maps always ran afoul of the Voting Rights Act “preclearance” requirement.