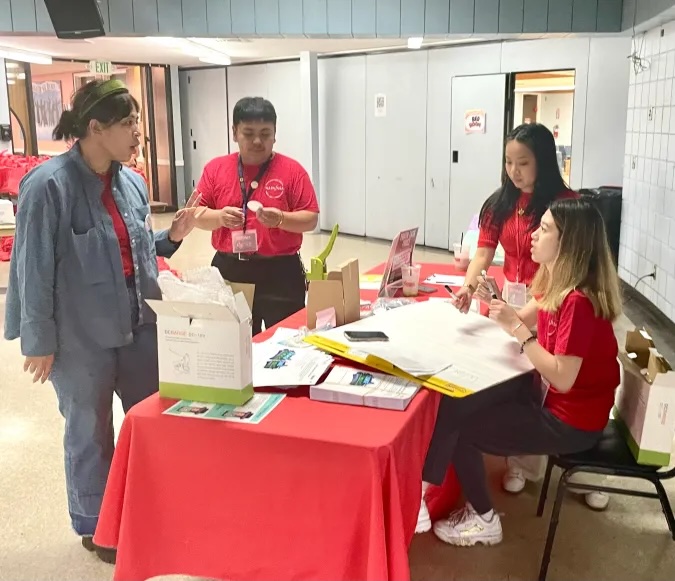

Above: Yuri traveled from Huntington Beach to participate in the arts festival in Monterey Park. Credit: Agustín Durán | Impremedia

By Agustín Durán | La Opinión

The teacher asks participants to close their eyes and breathe deeply to arrive at a place of connection with themselves and their surroundings. Another teacher invites participants to draw those emotions that might otherwise be difficult to express.

These are just some of the experiences that dozens of young teens and older adults shared as part of the Healing HeARTS Community Art Festival in Monterey Park.

“The problem is that we’re living in a very divided world,” says Marielle Reataza, executive director of National Asian Pacific American Families Against Substance Abuse (NAPAfASA), which organized the May 4 festival at the Langley Senior Citizen Center.

“Both in politics, immigration, racism and even at the global level. There are also intergenerational differences, all of which can make it hard for communities to sit down and talk about how we find a way out of these problems together,” she adds.

Intergeneration healing

Monterey Park, located in the western San Gabriel Valley in Los Angeles County, was the site of a mass shooting in January of last year at a popular dance hall that claimed 11 lives and injured nine others. Most of the victims as well as the perpetrator were Asian American.

Reataza points out that the theme of this year’s event is “Difficult Conversations,” noting that she’s heard from a majority of residents that they simply don’t know how to broach these subjects in conversation and that many prefer to avoid them altogether.

She adds that in the Asian American and Pacific Islander community there is a great deal of respect given to elders. Combined with cultural and language barriers, that can often make it hard to communicate when it comes to thorny issues like hate, racism and mental health.

“Many of our older adults who are immigrants didn’t know what a hate crime is, or that they had certain rights,” says Reataza, an immigrant herself of Filipino and Chinese background from the Philippines.

Reataza also says that on top of all these complexities is the reality of social media which can make it even more difficult to put discussions like this on the table, instead fomenting conflicting ideas taken from popular platforms that can deepen existing divisions among community members.

Activities at the festival included workshops with titles like, Empower and Protect, Spoken Word to Heal, Dance from the Heart, How Do We Talk and Self-Help Zine. There were also presentations and panel discussions with audience Q&A, all in a safe, friendly, and positive environment that invites healing, connection and the power of expression through art.

Pía Vasquez, 24, is a program coordinator with NAPAfASA and helped organize the fair, which she says was open to anyone age 15 or older from all backgrounds. “What we bring are alternative paths to healing,” says Vazquez, who is Filipina. “We want young people to practice something new, something maybe they hadn’t experienced before, especially now with all the distractions and worries around hate crimes, insecurity and climate change, among others.”

Responding to the rise in hate

Vasquez stresses that with all the worries young people have it can be hard to focus on and prioritize the things that really matter, but that when they have a chance to approach art it can be really beneficial in terms of expressing these emotions, and in having those tough conversations with family or friends.

According to Vasquez, the festival was inspired by the dramatic uptick in hate crimes that began during the Covid 19 pandemic (Los Angeles saw a 76% spike in hate crimes during this period) and by the aftermath of the shooting in Monterey Park which occurred during Lunar New Year celebrations.

The situation in the community had become so concerning that event organizers decided to do something immediately to unite residents, to bring them together to discuss possible solutions during moments of tension, insecurity and division that so many were living through.

Last year marked the festival’s first annual event, held at the Lai Lai Ballroom & Studio, the site of the shooting. “We decided on that location because we wanted to have a community healing event, we wanted to dance and have a positive experience in that place.”

Vasquez emphasizes that there are other challenges that could be more cultural or generational and are due to the lack of communication that sometimes exists between young people with their parents, a situation that hinders complex conversations between parents and children.

Crimes go unreported

The number of hate crimes targeting LA County’s Asian American community fell in 2022, according to the latest data from the Los Angeles Human Relations Commission, which showed a total of 61 for that year, down from 81 the year prior. Still, the lower number marks the second highest ever reported for LA County.

The commission’s report also notes that the figure is misleading, given the number of incidents and crimes that went unreported due to cultural or linguistic barriers, unfamiliarity with reporting a hate crime or, in some cases, victims’ immigration status.

‘Victims for decades‘

Bill Chan, 65, is originally from Singapore. He took part in the self-defense workshop and says he was very happy with what he learned and that he would like to see these workshops extended to more of the community given that Asian Americans are often targeted and have been for decades.

“Older seniors are among the groups most targeted because we’re seen as frail,” he said. “The issue is that because we don’t speak English we don’t report these incidents to the police.”

Many people began to target Asian Americans after losing their jobs during the pandemic, going after people, homes and whole communities regardless of whether they were Chinese, Japanese, or Vietnamese, among other ethnicities.

“We need more programs like this, full of positivity to reduce the hate,” says Chan. We know we can never eliminate hate completely, but we can reduce it and in this way, people will start to understand that we have to coexist as a society.”

Yuri, 22, is Vietnamese American and traveled from Huntington Beach to attend the event, which she said caught her attention.

“Every time I leave the house, my parents worry that something could happen to me,” she explained. “That’s why I think these types of programs are a way to connect with other Asian Americans in the community, have a conversation with other people and share your worries.”

This resource is supported in whole or in part by funding provided by the State of California, administered by the California State Library in partnership with the California Department of Social Services and the California Commission on Asian and Pacific Islander American Affairs as part of the Stop the Hate program. To report a hate incident or hate crime and get support, go to CA vs Hate.